Brazilian Composers: Beyond Villa-Lobos

European classical music arrived in the world's fifth largest country with the Jesuits, who brought with them the sacred polyphony of Palestrina and Victoria. Those young men who showed musical aptitude were trained not only as priests but as singers and composers.

Most of their work is now either lost or forgotten, but the Requiem by José Maurício Nunes Garcia (1767-1830) is a powerful exception, albeit evidently written in the shadow of Mozart's example. Sony's download-only version led by Paul Freeman in its 'Black Composer Series' from the 1970s is still the most polished of several recordings.

Gold Rush

The classical tradition became another badge of secular bourgeois status during the 19th century. Royal patronage and gold-rush money built opera houses in remote outposts such as the Teatro Amazonas in Manaus, thousands of miles up river from the cosmopolitan centres on the east coast of Brazil. The emperor of the day, Pedro II, even suggested to Wagner that Rio should host the premiere of the opera Tristan und Isolde.

However, even native audiences did not regard Portuguese as a fit language for art music, and almost half a century passed before Alberto Nepomuceno composed the first Brazilian opera worthy of the title, a one-acter (Artemis, from 1898) drenched in the heady perfume of Wagnerism.

A YouTube search should certainly turn up a couple of in-house performances, but Nepomuceno's importance as a pioneer of a distinctively Brazilian style takes shape on a recent Naxos album [see Essential Recordings], which is the first in a huge projected series of 'Music from Brazil'.

As the balance of cultural power shifted from Berlin to Paris in the early decades of the last century, so did the destination of study for young Brazilian composers. Back home they fell under the spell of Mário de Andrade (1893-1945), a symbolist poet, novelist, musicologist and art historian.

In 1922 he curated a Week of Modern Art in São Paulo that became a watershed for Brazilian culture of all forms. He regarded the previous attempts to spice up European classical genres with native elements as just one step towards the flourishing of a musical culture that Brazil could be proud to call its own. With his encouragement, Camargo Guarnieri, Francisco Mignone and Cláudio Santoro and others emulated the examples of Nielsen, Sibelius, Bartók and Vaughan Williams in Europe.

Still Magic

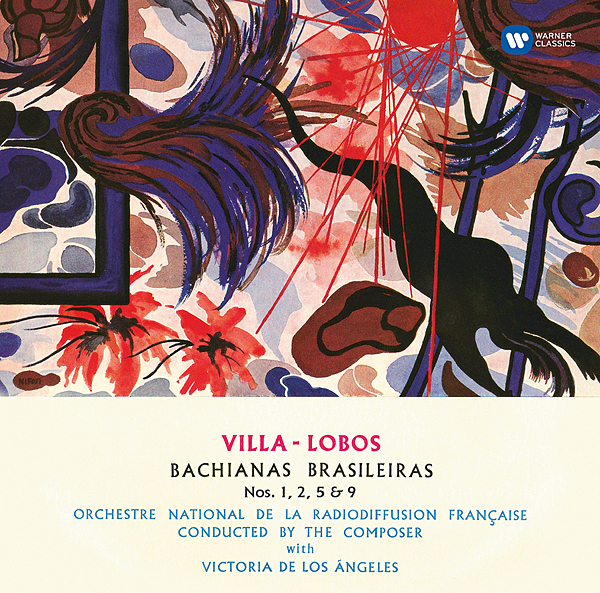

In this regard, the music of Heitor Villa-Lobos is an outlier. And yet for listeners above the age of 50, the sensuous world of Brazilian classical music was long defined by a single EMI album, of Villa-Lobos conducting his Bachianas Brasileiras, with Victoria de los Angeles floating the vocalise of the Fifth above an octet of swaying cellos: still magic in its latest Warner Classics reissue [2435669122].

The composer's French-made recordings deserve their definitive status despite the rocky ensemble and spotlit engineering in both mono and stereo. EMI/Warner is still a first port of call for his music, even if you can't locate either of the deleted 'Villa-Lobos conducts Villa-Lobos' or 'Villa-Lobos par lui-même' boxes online, for the '80s digital recordings by the Mexican conductor Enrique Bátiz – there's a useful 3CD set [5008432].

Listeners to Guarnieri and Santoro in particular will find that Villa-Lobos was just one chapter of the novel. The Paris-trained Guarnieri also composed classical versions of native genres such as the chôro (a cry or lament, but often quick and upbeat in mood), less immediately catchy than his better-known contemporary but also more sinuously crafted. He is a Brazilian Prokofiev to the Shostakovich of Santoro, whose 14 symphonies (1940-89) experiment with form while being consistently charged with the tension and long-span satisfaction that we expect from any major symphonist.

The local Festa label issued collectable LPs of music by Santoro, Mignone, Radamès Gnattali (named after the male lead in Aida) and many others. In the CD and streaming era, Selo Sesc makes albums that are often stronger on musical appeal and rarity value than engineering finesse.

Anyone plugged into Spotify should stop reading now and head for the Selo Sesc playlist of 'Música de Concerto', kicking off with Gnattali as guitar soloist in the Suite Retratos by Chiquinha Gonzaga, which to these Anglo-Saxon ears pours the sharp, giddy scent of a strong caipirinha into an irresistibly carefree sequence of native and European dances.

Most Brazilians think of classical music first and foremost in orchestral terms. The nature of the collective endeavour taps into a native feeling for mass-participation forms of culture such as drumming groups, volleyball and futebol. The string quartets of Nepomuceno, Villa-Lobos and others rarely extricate themselves from a Brahmsian grammar, though the recordings by the Brazilian String Quartet (on Albany Records) and the more up-to-date Quarteto Carlos Gomes (Selo Sesc, download only) are well worth investigating on their own, anachronistic terms.

Piano music and pianists have been better served by Brazil's relatively young conservatoire tradition; Nelson Freire and Cristina Ortiz are not the only soloists to enjoy international careers. Rio born, now based in London, Clélia Iruzun accompanies Anthony Flint on a sensitively engineered new Somm album [SOMMCD0632] of post-Romantic violin sonatas by Henrique Oswald and Leopoldo Miguez.

Sideways Look

The same label plays host to Iruzun's magnificently uninhibited performance of the Piano Concerto [SOMM265] which Mignone could have written as a missing link between Rachmaninov and Prokofiev, balancing big tunes with city-life bustle and fistfuls of keyboard bravura.

Postwar Brazilian classical composers took a sideways look at the techniques of European modernism, many of them taught by the Swiss émigré Ernest Widmer. A pupil of Guarnieri who died in 2010, José Antônio de Almeida Prado found a contemporary voice through the Romantic apparatus of the piano much as Messiaen did in France.

If the scale of his Cartas Celestes (4CDs on the Grand Piano label) proves intimidating, try the half-hour, nine-section span of his Piano Concerto No 1, which is another fine modern Naxos recording [8574225]. Phantasmagorical and efflorescent in its quieter sections, it is like a Bartók nocturne transplanted to the upper reaches of the Amazon.