Aiwa Micro Series 30 system

The mini/micro system craze was one of the Japanese electronics industry’s last great flourishes of the 1970s. Aiwa joined with Technics, Toshiba (Aurex) and Mitsubishi in producing tiny equipment with the same (or better) performance than many full-sized units, the contention being that improved component miniaturisation meant large boxes were no longer needed.

Aiwa’s 22 micro series was introduced in mid-1979 and proved to be a big hit. It couldn’t quite match the finish of Technics’ Concise Components range or the outstanding performance of the Toshiba/Aurex System 15, but it was fully featured, keenly priced, visually attractive and decent to listen to. It was especially popular in Germany, where it was also offered by BASF, Wega (then part of the Sony Corporation, just like Aiwa) and Uher, which applied orange fascias to give it a distinctive European look. Yet it lasted only a year in the market, replaced in 1980 by the 30 series micro system seen here.

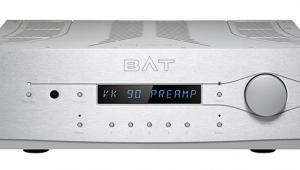

The fully featured SA-C30 preamp [top] and SA-P30 power amp [bottom] formed one half of Aiwa’s M-301 (30 series) system

In practice there were two systems, both with the SD-L30 tape deck and ST-R30 AM/FM tuner, but with either the 2x15W SA-A30 integrated amp or the 2x35W SA-C30/SA-P30 pre/power tested here. In addition, Aiwa offered its AP-D35 and AP-D50 turntables, oak-effect cabinet, and SC-E1/SC-G33 speakers.

Fine-tuned

Differences between Aiwa’s 22 and 30 series models were subtle, but important. The SD-L30 tape deck, which otherwise looked similar to the SD-L22, had a Metal tape facility – an increase in bias power, a new design of recording head and changes to the equalisation and switching were all required. There were no significant functional changes from the ST-R22 tuner, although the new ST-R30 was slightly deeper and a Longwave AM band was offered in some markets.

The SA-C30 preamplifier was also slightly deeper than the SA-C22 it succeeded, the latter’s electronic signal routing replaced by conventional mechanical switching which brought a simpler, purer signal path and slightly improved sound quality. Yet it was the SA-P30 power amp that witnessed the biggest uplift. The rated output was now 2x35W instead of 2x30W, as evidenced by a subtle recalibration of the five-step LED power meter.

None of this was of any real consequence, but the layout of the new circuit was completely different. The close relationship between Aiwa and Sony resulted in technical similarities between the Aiwa SA-P22 power amplifier and the power stages of Sony’s TA-P7 miniature integrated model. Admittedly, Sony’s amp used an electronic ‘pulse’ power supply and Aiwa stuck with a linear PSU, but the power stages of both were designed around Sony’s CX-171 driver IC and a pair of substantial bipolar transistors. The SA-P30 changed this arrangement around, with an all-discrete driver stage and a hybrid module for each channel containing the power transistors and the biasing circuit. In addition, better low impedance (4ohm) drive was achieved [see PM's Lab Report] and the facility was added to run the SA-P30 in bridged mono mode, this being rated at 2x70W/8ohm.

Stack ’em up

These Aiwa units may be tiny but they look and feel like proper hi-fi. Each is fully independent and could be used as part of another system, as they all have built-in mains power supplies and use standard RCA connections at standard signal levels. The little rack-mount handles make each piece look suitably ‘technical’, although, without screw holes, this was an aesthetic feature only. The units could be stacked in any way, but note the cassette deck has a little door in its top cover to give access to the heads for cleaning.

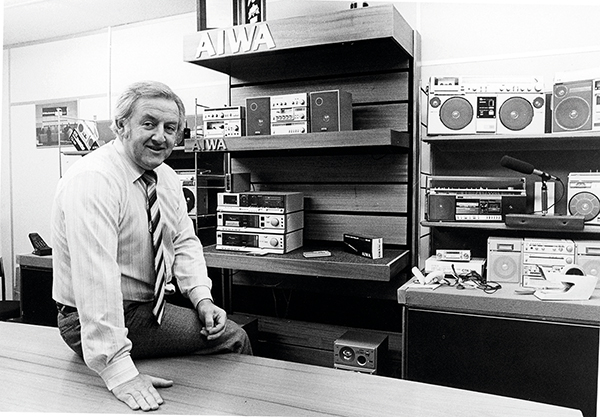

Seen on the top shelf in 1980, behind Mike Emery, Aiwa’s Sales Director, is the M-302 system which combined the SD-L30 tape deck and ST-R30 tuner with the SA-A30 integrated

Everything works exactly as one would expect, except for the SD-L30 tape deck which features a slot-loading mechanism, not unlike a cassette player in a car, and has five large piano key controls. Loading a tape turns the motor on, putting the deck into pause. The play/pause key starts and stops the tape, and has a very light action as it simply lifts and lowers the pinch roller. Fast-forward and rewind keys are conventional but the stop key also ejects the cassette, something that it is all too keen to do if it is pressed too heavily!

Oddly, Aiwa’s mechanism has no facility to read the erase protection tab at the rear of the cassette, meaning you could accidentally record over a pre-recorded tape. To reduce the chance of this happening, the record key can only be pressed if no cassette is loaded; you press the key and then load the tape, presumably after carefully checking its contents.

The SD-L30’s record key then latches and recording starts and stops with the play/pause key. To listen to the recording you can press stop and release the record key, but to resume recording you have to take the cassette out and start again. Fine for simple, one-off recordings, but you wouldn’t want to do anything more complex.

The rest of the tape deck’s specification is generous, including manual selection for Normal, Chrome and Metal tapes; Dolby B Noise Reduction, manual record level control with a five-segment/three-colour PPM display; a built-in stereo microphone amplifier; and electronic auto-stop in all modes.

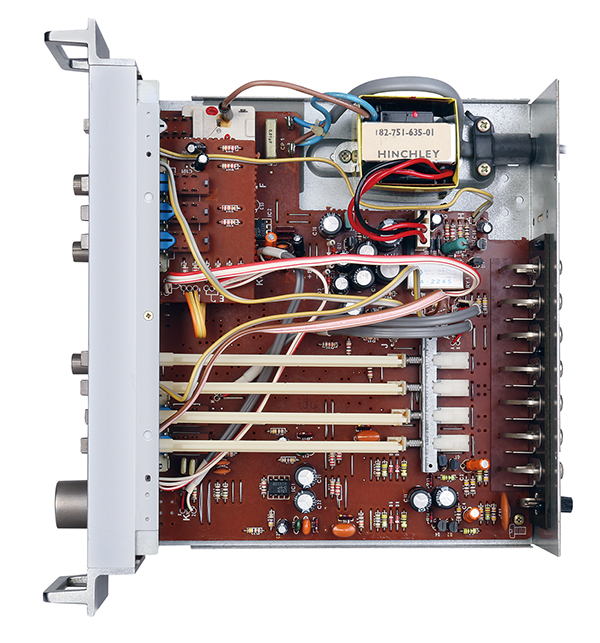

Inside the SA-C30 with remote (mechanical) switching via plastic rods, discrete phono stage [bottom right], tone circuit [top left] and op-amp line stage [bottom left]

Aiwa’s partnering ST-R30 tuner is far more conventional. It looks like a digitally-tuned model but, in fact, the tuning is mechanical, complete with a cord drive and a beautifully engineered variable gang capacitor inside. The digital display is just a frequency counter readout – you can’t automatically search for stations or store them – and there is no facility for listening to weak FM stations in mono. However, you can choose the ‘hi-blend’ facility instead, which trades stereo for a quieter mono sound if the signal is particularly weak. Inter-station muting is offered on FM as well.

By comparison, the SA-C30 preamp is really comprehensive. It offers inputs for the system’s tuner and cassette deck as well as a turntable (MM cartridge type) and two auxiliary sources. There is also a useful –20dB attenuator as well as a less useful rumble filter and loudness function. Incidentally, both the SA-C30 and SA-P30 are fully DC-coupled throughout. Well resolved circuitry means that there are never any pops, howls or bangs regardless of which order any of the components are switched on or off.

![]() Tim Listens

Tim Listens

The Aiwa 30 is a compact but impressive performer. Dealing with the sources first, the SD-L30 cassette deck sounds as good as you would expect an Aiwa design of this era to be. It is pitch stable and clean-sounding, even with pre-recorded material. It can’t match Aiwa’s top models like the AD-6900, but for what it is it does the job well. Recordings made on premium ferric tape (I used TDK AD-X) reached a good standard too, although the small and rather basic peak programme meters made accurately judging recording levels quite difficult.

Aiwa was well known as a leader in cassette technology but was less well regarded for its tuners, although it did produce a number of statement models, such as the full-size AT-9700. Some of this thinking must have been shrunken down into the ST-R30, as it too works extremely well. Sensitivity is excellent and it can produce noise-free stereo reception on FM without the need for extravagant aerial systems. The circuitry is unusually complex for such a small unit and it seems as if nothing has been left to chance. BBC Radio 3’s live concerts sounded spacious and expansive though the ST-R30, and in the context of the rest of the system one couldn’t ask for more.

Bright idea

Sources aside, the tiny Aiwa’s sound is dominated by its amplifiers. The auxiliary inputs are well engineered and can accept any modern line level source, although the sensitivity is perhaps a little high so the –20dB attenuator button is a must for low-level playback. Critical listeners will note that the sound improves over the first half an hour of use, being a bit hard and ‘clanging’ to begin with. Once warmed up the two units still have a bright sound, plus an excellent sense of focus. Treble is fully extended and while you would never call it smooth, there is at least a reassuring freedom from glare and grain.

Vocal clarity reaches a high standard too, although a subjective dip in the response in the mid to lower bass can leave deep voices and low toned instruments sounding a bit cold. Things seem to recover for the lowest octave, which is reproduced with plenty of articulation and punch.

Screened PSU transformer and reservoir caps dominate the SA-P30’s interior with integrated power amp modules bolted to the heatsinking [top and bottom]

Judged against the highest standards I did feel that Katie Melua’s vocals in the title track from Call Off The Search [Dramatico DRAMCD0002] sounded slightly metallic when played through Aiwa’s system, but the overall sharpness and crispness still made the album a joy to listen to. The sound has a sense of immediacy, grabbing one’s attention every time the music changes key or when a new instrument is introduced to the mix. I’ve heard more expensive and elaborate equipment that cannot do this with such apparent ease.

Special delivery

Orchestral pieces are also made exciting by the Aiwa system’s sharpness and ability to bring transient sounds to the fore. The overall tonality tends to accentuate brass and strings in preference to giving a realistic impression of concert hall ambience, but with well chosen and well positioned loudspeakers the soundstage is impressively broad and deep. It can be difficult to believe that such a mighty performance of a piece like Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 [Denon 38C37-7060] can come from such a tiny piece of equipment and still sound credible, but that is one of the things that makes the best Japanese micro systems so special.

The Aiwa 30 wasn’t the most expensive system of its type (it cost only a third as much as the top Aurex set-up, for example) but it can still give many of the full-sized alternatives a run for their money. Aiwa’s promotional literature of the time referenced excellent performance through large monitor-quality loudspeakers, and on test it’s difficult to disagree. Careful matching is the key, but as the components are so small you’ll have plenty of room for a really large pair...

From the top – SA-P30 has RCA ins, speaker impedance and BTL settings plus spring-clip and DIN speaker outlets. SA-C30 has three line ins, MM in, a tape loop and pre out (all on RCAs). SD-L30 has mic sockets and line in/out on RCAs. The ST-R30 tuner has an attached bar antenna, AM/FM aerial inputs and line outs on RCAs

Buying secondhand

Aiwa micro systems of this era are still quite common, but there is a bewildering range of models and permutations to choose from, so – as always – be sure you know exactly what you are buying.

Apart from the muting relay in the SA-P30 amplifier (which will need cleaning if one or the other channel is weak or intermittent), each of the units is quite reliable. Like any cassette deck, the SD-L30 will require occasional maintenance to keep it on top form. It is also fiendishly complicated, and with its densely packed components and assemblies is very difficult to work on. Even replacing the belts is something of a challenge, although it can be achieved if both time and care are taken. The heads are made from Permalloy, which isn’t the most durable of materials, so check for wear in well-used examples.

Hi-Fi News Verdict

On test some 44 years after it was launched, Aiwa’s series 30 system proved why it was so popular with consumers back in its day. There really isn’t a weak member of the team here as all the units pull their weight, contributing to a very well balanced package. It’s perhaps not the ultimate in micro/mini hi-fi but still remains a fine example of what was possible. In short, the series 30 is now very collectable...

Sound Quality: 80%