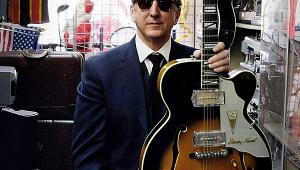

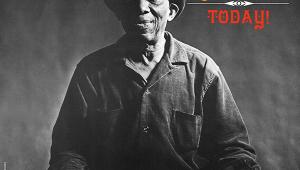

Norman Smith Page 2

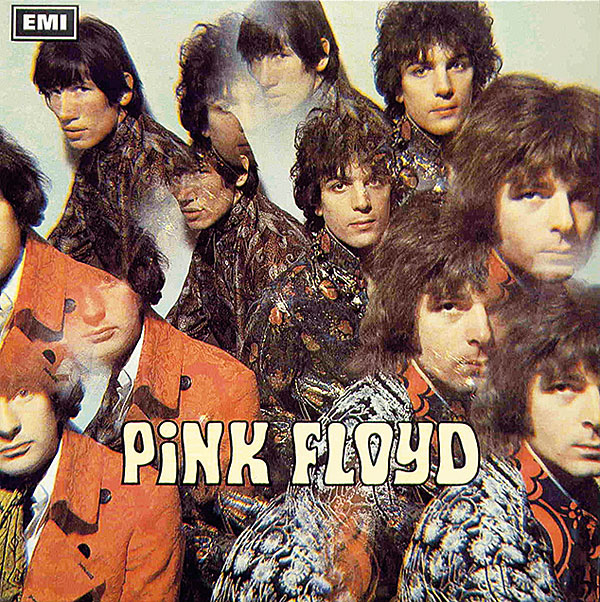

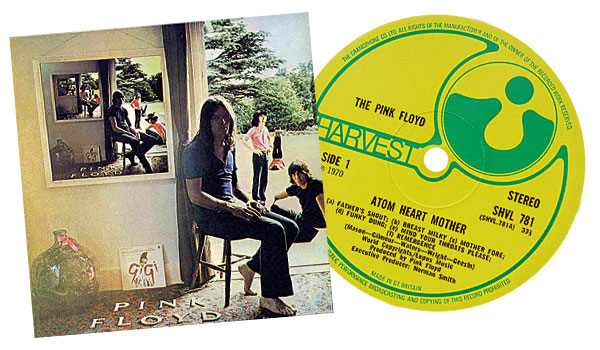

'What I saw absolutely amazed me,' he recalled. 'I was still into creating and developing new electronic sounds in the control room, and Pink Floyd, I could see, were exactly into the same thing…' Smith persuaded EMI to offer a very high advance payment, £5000 against royalties, and, after Joe Boyd [HFN Oct '16] had done their first one, 'Arnold Layne', he produced the group's second hit single, 'See Emily Play', and went on to produce the Floyd's first four albums – Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, Saucerful Of Secrets, Umma Gumma and Atom Heart Mother.

'With The Beatles we're talking about something really melodic, whereas with Pink Floyd, bless them, I can't really say the same thing for the majority of their material. "A mood creation through sound" is the best way that I could describe them,' he continued. 'In fact, I could barely call it music, given my background as a jazz musician and the musical experience that I'd had with The Beatles. Still, there was something about Syd Barrett's songs that was indescribable – they were nondescript, but obviously had that Barrett magic for an awful lot of people.' Syd, of course, was slowly spinning out into his own orbit, and Norman spent a lot of time trying to keep him in the zone. 'I got along as well as anybody could with Syd... He really was in control. He was the only one doing any writing, he was the only one who I, as a producer, had to convince if I had any ideas.

'But the trouble with Syd was that he would agree with almost everything I said and then go back in and do exactly the same bloody thing again! I was getting nowhere.

'I never actually saw him taking drugs in the studio, but he had the kind of character that, even if he hadn't taken any, you'd think he was on drugs. He was a peculiar person. You couldn't really hold a sensible conversation with him for longer than 30 seconds. Roger Waters had the best rapport with Syd, but even he found it difficult.'

Out The Door

'I remember them being on Top Of The Pops with "See Emily Play", and beforehand I took them into Number One Studio purely to rehearse what they would do on television for the first time. I was almost choreographing them, silly little old me, thinking they would actually stick with my choreography! Of course, that all went out of the window, thanks to Syd.

'He wasn't happy about doing Top Of The Pops. He didn't like singles – he only liked doing albums – and it was while waiting around for an appearance on Saturday Club [a BBC radio show] that he walked out of the door and went missing. That really was the first sign of his complete mental breakdown, and he never did come back into the studio any more after that.

'As musicians, the Floyd were capable enough, but Nick Mason would be the first to agree that he was no kind of technical drummer. In fact, I remember recording a number – I can't now recall which one – and there had to be a drum roll, and of course he didn't have a clue what to do. I had been a drummer, and so I had to do that. Nick was no threat to Buddy Rich!

'Roger Waters, on the other hand, was an adequate bass player for what they did, but to be honest he used to make more interesting noises with his mouth. He had a ridiculous repertoire of mouth noises, and we used that on one or two things.

'So, they were capable, but I had a great struggle with them after Syd Barrett went funny and left,' Norman continued. 'They tried very hard to write material. I remember them writing a song about apples and oranges, which I dressed up and released as a single, and that sold about six copies.

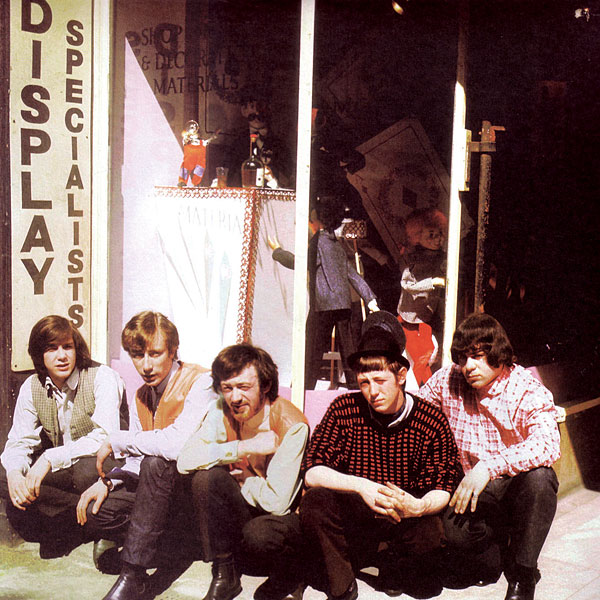

'It was around the time of the Saucerful Of Secrets album, and I really did think that it was all over. We still had to keep the singles coming for the audience that they'd established, but... their recording career was going down the drain fast. And then along came Dave Gilmour and things picked up again.' When he didn't have his hands full with the Floyd, Norman also mentored The Pretty Things, helping the sessions for S.F. Sorrow, the 1968 album generally regarded by rock historians as the first concept album recorded in the UK. He also produced Barclay James Harvest, taking control of their early breakthrough LPs: Once Again (1971) and, later that year, And Other Short Stories.

Like A Hurricane

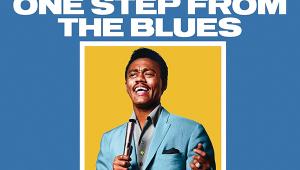

And then something very odd happened. Norman had written a song he thought would suit John Lennon. He played it to a mate, who just happened to be the famous producer Mickie Most [HFN Sep '17]. On hearing it Most insisted that Norman should record and release the track himself rather than pass it on. So our Norman, under the moniker Hurricane Smith, found himself at No 2 in the UK charts with his single 'Don't Let It Die'.

He then followed this swiftly with a cracker called 'Oh, Babe, What Would You Say?', which reached No 4. Norman was now a bona fide pop star at the ripe old age of 48!

He passed away in 2008, a remarkable man under whose guidance British music blossomed into the envy of the world.