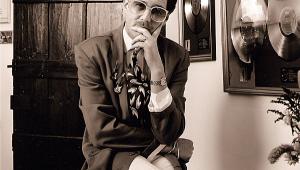

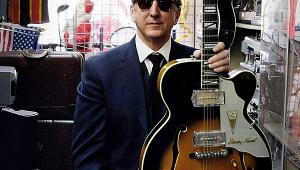

Nick Lowe Page 2

'They came into the studio and set up and played and all I did was just switch everything on and watch them do it,' was how he recalled those sessions. 'The people I was working with then were all in their teens or early 20s. As far as they were concerned, I was this real experienced old cove, but I didn't really know anything about anything.' Except, of course, he did. What he had was an ear for a great performance and the knack of creating a vibe in the studio that enhanced the mood of the songs, not to mention the nerve to trust the songs themselves. So he left them to breathe, uncluttered.

His modus operandi? 'I wanted to make records live in the studio and I wanted to do it so it felt good and soulful. I thought it was real important to sing the vocal at the same time because that brings it a tremendous amount of feeling, a sense of performance. I believe that if you sing the thing at the same time, this other element comes into the room and the music sort of moulds to the vocal much more apparently than if you just sing the vocal on top of a backing track.'

Gold DustOthers were not convinced: 'When I tried doing it, the engineers and people I worked with were kind of patronising about it, saying, "That'll do for now. We'll do the vocals properly later". But I said, "Oh no, no, no! That is going to be the vocal". And they'd go, "Really? What, with that little wobbly bit?". "Yeah, absolutely with that little wobbly bit, when it goes off pitch. I like that". Having the personality in there is gold dust.'

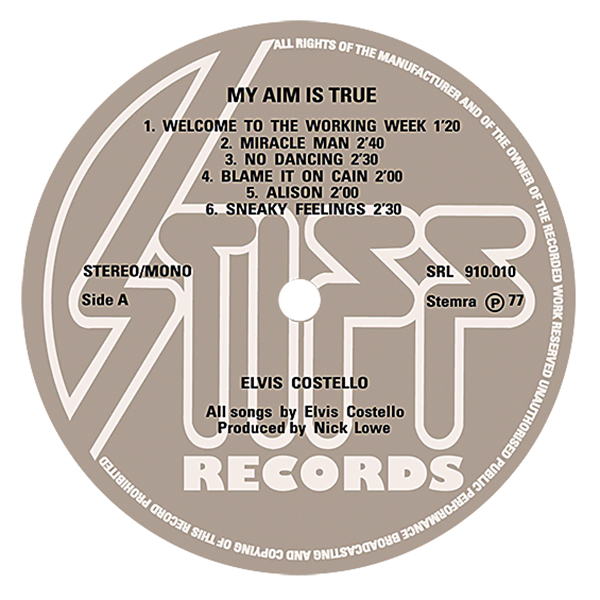

Basher's favourite place to work was Pathway, 'a tiny studio in Stoke Newington. It was like a garage. It had been Oswald Mosley's lock-up, where the Blackshirts kept their pamphlets and placards! It was completely analogue, all glowing valves, and was boiling hot in the summer and freezing cold in the winter, but it had a fantastic sound'. It was here Lowe recorded Elvis Costello's My Aim Is True, in 16 hours flat. It took another five to mix. Total cost: £800!

Monkey Business

Ever modest concerning his abilities, Basher recalls his halcyon days thus: 'I can't actually recall what, if anything, I did, because I do recall I would kind of… sit around all day smoking cigarettes, drinking and cracking the odd joke until it was time to go… It was still old-school, in the sense that if you said you were a producer forcefully enough, people believed you.

'You didn't have to know how to actually work the equipment. I didn't do much knob twiddling but I was good at telling the engineer what I wanted to hear, and at energising people, figuring out what they wanted to do, and at discovering where the creativity in a band lay – that it wasn't necessarily with the loud-mouthed lead singer but with the shy bass player.

'I wasn't always right, I made bad decisions, but I was full of myself and the more people wrote how good I was, the more I believed it.'

As for the days when the Stiff label was starting to make waves, Lowe has fond memories: 'It was an exciting time because, for a while, the monkeys took over the zoo. Suddenly big heads started to roll in the major labels. People who we thought were ruining the music scene were clearing their desks. Goodbye! Then they got in hip-looking guys, though they weren't really hip, and eventually the majors wrested back control.'

Lowe doesn't do much production any more, apart from working on his own recordings. He kind of retired from that part of the business in the late 1980s to, as he put it, 'escape the tyranny of the snare drum'. His bashing days, it seems, were over.

'The trouble is that a lot of people don't like hearing mistakes and spontaneity in records – it makes them really nervous. The general public has gotten used to hearing flawless recordings. You can make a perfect-sounding record in your bedroom, and unfortunately most people do. Even if it's a really dreary song, you can make it sound like it's all going on.

'If everyone's record is "good" it means that it all kind of sounds bad or bland. So if you hear a "bad" record, something that sounds really funky, it can sound like a work of art.

'Most contemporary pop music has got a sound frequency they use, it's very digitalised. The sound frequencies disagree with my ears. Also when I hear auto-tunes and things like that, it doesn't sound very good to me… I'm so stuck on the way I like to make records, and I can't really do it any other way. Most records are made in a fashion now that I don't really have any interest in, in a much more clinical kind of way. 'Don't get me wrong, the new technology is great. It's not like I'm a Luddite – "Oh, we should all still be recording onto wax cylinders" – or something like that. I like the new technology, but I think one shouldn't be a slave to it. One should use it to make the music come alive as opposed to just making it sound perfect...

'I have never been one for dividing things into genres; s***t music is s***t music and a good song is a good song. I like to think of my stuff as 'fly', or 'saucy'. Those words will do fine.'

Legend Returns

For your information, the way our story started has a very happy ending. The musical legend returned to play the Albert Hall some 12 years after that song's unhappy debut, having occasionally checked in on the writer's progress. One night he called our hero up on stage to play with him. Still copping the buzz when he got back home, our hero picked up his guitar and the rest of the verses just poured out of him.

With no little trepidation, he sent it off to the legend but didn't hear anything back for awhile until suddenly there it was, on an LP at last. The legend was Johnny Cash. The album, American Recordings. And the song? 'The Beast In Me'.