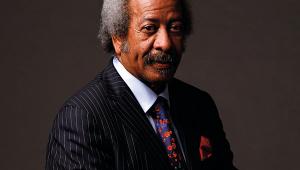

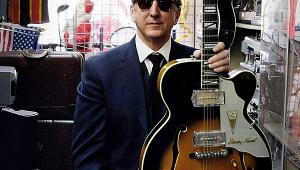

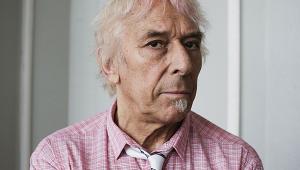

Glyn Johns Page 2

'You can't do what I do and be under the influence of anything,' Johns declares. 'Coffee would be about it.'

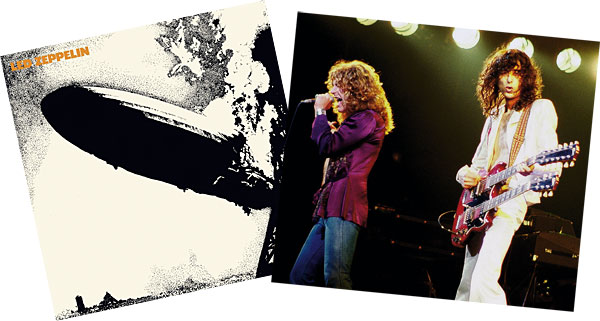

It was this work ethic that prompted Jimmy Page to call him up in 1969 to help launch a brand new project. 'I'd known Jimmy forever,' Johns recalls. 'We came from the same town, Epsom, Surrey, and we'd even had a little band together for about five minutes. I'd got him a few sessions in the past, and when he decided to put Led Zeppelin together he asked if I was interested.'

Thunder In A Bottle

'The sessions were actually booked under the name of The Yardbirds and I had no idea what it would sound like, but when they started playing I was completely blown away.

'I don't think I've come down yet from the buzz I got from being in the room, it was utterly inspiring and incredibly simple to record. They were well rehearsed and masters at what they did, which is why it took only nine days, including mixing. I was helping put The Stones' Rock And Roll Circus together around the same time, and I took an acetate of the album into a production meeting. I said, “This is going to be huge”, but Mick [Jagger] wasn't interested in hearing it, so I dragged George Harrison into Olympic to listen to it on the way back from a Beatles session. He didn't get it at all, which I thought was extraordinary. Too set in his ways, maybe.'

It was during these sessions that Johns devised the drum sound for which he is justly revered. Utilising four microphones, his innovation was to place two mics overhead, equidistant on either side of Bonham's snare, creating a sound which has been described as 'like catching thunder in a bottle'.

Johns came to work with The Beatles on what turned out to be Let It Be, towards the end of their days, when George Martin had been sidelined, fed up with the band's infighting.

'I'll never forget when the call came. This Liverpudlian accent introduced itself as Paul McCartney, and I thought it was Mick Jagger taking the p**s! It was fascinating to see The Beatles just playing as a band rather than creating a record the way they used to.

'The idea was to rehearse new material and then do a live show which would be filmed at some Roman amphitheatre in North Africa. But they ended up on the roof of Apple in the freezing cold! It was great seeing the personalities interact with one another, but bits of it were a little unpleasant. It was rather sad to see what was going on. George and Paul were bickering but it was more to do with exceptions being taken to Yoko playing such a large role. It was a little awkward, and there was so much else going on I don't think the album took precedence. It was disappointing that the record was never released as I finished it. John took it to Phil Spector, who proceeded to puke all over it. It was just awful.'

A New Moon

A New Moon

The Who's Who's Next was hardly any easier. 'I knew them because I'd engineered “My Generation” and all that early stuff. I'll never forget recording “Won't Get Fooled Again” in the hall of Stargroves, Mick Jagger's house in Newbury. There have been a few tracks during my life where the hairs stand up on the back of your neck and you think, “Jesus Christ!”. That was one.

'My job was to try and make sure that the other members of the band were satisfied with their involvement while still trying to keep intact what I believed the material required and what Pete Townshend wanted for it. That was very difficult. John Entwistle was critical because I made him play with a much more regular style and sound.

'It was the same with Keith Moon. Some of the material didn't require mayhem, it required a bit more thought and control, and that wasn't his natural way of playing. It was hard to get everyone to see the bigger picture, but I don't think you could say Who's Next doesn't do the band justice.'

Yet another awkward task was rescuing Combat Rock, originally a prospective double, from the clutches of The Clash. Johns, a senior member of the old school, despised punk's non-musicality but nonetheless pitched in with heartening results.

'I don't think I've enjoyed working with anyone as much as I did with Joe Strummer,' he recalls. 'A lovely bloke and unbelievably talented. He and Mick [Jones] had been in a New York studio for two weeks trying to mix the record and it hadn't worked out, so I was asked to mix it. Although punk had never appealed to me, I was astounded by the music's skill, ingenuity and humour, and the quality of the lyrics. But it was a hell of a mess.

'I started with Joe at 10am, and he was happy for me to get stuck in, edit, chuck stuff out. It was like fighting through the Burmese jungle with a machete. Then at 7pm Mick arrived and I played him what we'd done. He sat there with a sullen expression and criticised everything. I said, “That's a shame, but I'm afraid they're done. You were supposed to be here at 10am”. He got annoyed and left. There was a big row the next day then I just finished it with Joe.'

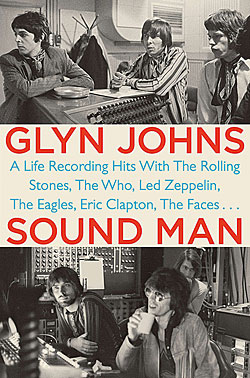

Other tales we've no space to tell here are Johns' involvement with Bob Dylan, Neil Young, The Faces, Jimi Hendrix, Steve Miller Band, Ryan Adams and… oh… tons more which you can redress by reading his autobiography, Sound Man, published by Plume.

Leaps And Bounds

Whatever the challenge, though, Johns' approach has always been consistent, disciplined and simple. The goal: to achieve an organic sound which requires, 'musicians who can play and artists who can sing, then wanting to achieve

a natural and musical sound.'

Another anecdote probably best sums him up. It's summer 1967 and The Beatles have just released Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Mick Jagger takes Johns to a cafe near Olympic Studios where The Stones are recording. Jagger is so stunned by the leaps and bounds that Pepper has taken, he's in full-on panic mode. He leans towards Johns and says: 'You've got to come up with some new sounds'. Johns looks him up and down and replies: 'Oh really? Have I? I thought I was here to record you playing.

'And that,' he concludes, 'has always been my attitude.'