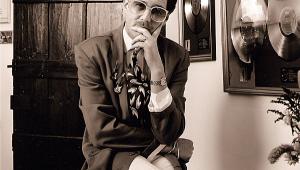

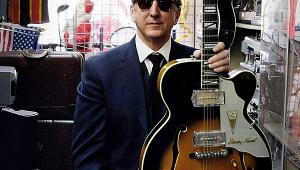

Dave Stewart Page 2

Faith Lift

Eurythmics moved their operation to the small entrance hall of a former church in Crouch End. When Sweet Dreams took off and the money started rolling in, Stewart bought the whole building and turned it into The Church Studios, recording most of the Eurythmics albums there until he sold it on to singer David Gray in 2004.

'We then got in a 24-track Soundcraft tape machine and a slightly larger desk, but we didn't ratchet up much else there gear-wise… It was just very exciting for us to have a lot more space to work in', he recalls. While he was away on tour, other artists such as Bob Dylan, Robert Plant, My Bloody Valentine and Radiohead took advantage of the space.

'What happened with me was, I was producing the Eurythmics records, and people started listening to them and going, "Hey, we like those a lot". Before you knew it, I was being asked to produce records for other artists. But that wasn't my plan.'

Planned or not, he began taking up the offers and soon found he brought something unique to the party. 'A lot of producers can play instruments, but they aren't performers,' he says. 'I know what it's like to go on stage with a band. I'm probably thinking like an artist when I produce somebody else's record. "What's this gonna be like live?". That kind of attitude can be very useful when you're trying to create excitement with a track.'

One such case is 'Don't Come Around Here No More' by Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers. Stewart co-wrote, produced and played on it: 'There's the part in the track where it explodes into this double-time thing, and the whole band kicks in and it goes into a frenzy. It was good for the song, but I was probably also thinking, "Hey, this will really work live, too".'

Tense Meeting

How he came to work with Petty is a pretty good example of Stewart's serendipitous approach. He was working on a song for Stevie Nicks and was messing around in the studio with a sitar hook. Tom Petty then happened to drop by and immediately decided he wanted the song for himself.

'His band were like, "What's this?". It was all my backing track until the end; I had done all of that with a drum machine in a hotel room in San Francisco. There's a lot on the track. I did the guitars and the sitar, some cello and viola. Tom put his vocals on and then the band did their part at the end, playing in double time.

'Tom and I became great friends after this. I think he'd been having a crisis, a bit of a roadblock finishing the album. But Tom just said, "Oh, f*** it, let's make a record". It was kind of weird, though – the album is called Southern Accents, and there's me playing the sitar.

Here's an even weirder example of the way Stewart works. He rocked up to visit his ex-wife, Peg and who should be there but her new boyfriend. The conversation was understandably tense until the newbie mentioned he wrote string arrangements. As an ice-breaker Stewart casually invited him to visit The Church to see if he could do anything with a song he was having trouble recording. The result? The sweeping strings that drive 'Here Comes The Rain Again'.

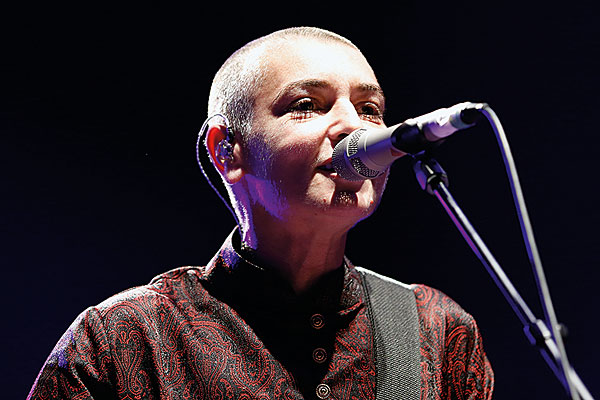

Over the years, Stewart has produced records by Aretha Franklin, Bon Jovi, Sinead O'Connor, Bryan Ferry, Stevie Nicks, Katy Perry, Joss Stone, Marianne Faithfull, Mick Jagger and Ringo Starr to name but a few. 'One of the secrets to my ability to collaborate with so many other talents is that I take all the pressure away…' says Stewart. 'When I come along and say, "Well, you know, it doesn't really matter if you don't like it. Nobody will ever hear it. We'll just throw it away, burn it. It doesn't make a difference", suddenly it's a whole new world.

'There is no pressure, and you're allowed to make mistakes. You don't have to think everything is precious. When you're relaxed, great things happen, and you can capture something truly amazing. And this creates momentum, because you use that energy and it leads to more ideas and inspiration.'

Against The Wall

There's also technique: 'I'm one of those old-fashioned record producers who likes to make music around the voice. People want to hear and feel the emotion in the human voice, and for me that's the most important thing to get right.

'There came a point when recording music when you could have 48 tracks, then 72 tracks or so, and just create a giant wall of music. And not a good wall of sound, like Phil Spector's – which was crafted always around the singer – but just a big wall with no dynamics that would overcome the voice. I believed in following the voice on its journey, and that's still my thing.

'In some ways, what I do is like being a dentist. I have to get something out of an artist.'