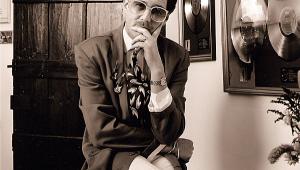

Burt Bacharach Page 2

'It may be about what the work is to start with, when you hold it up to the light,' he once said while discussing the enduring quality of his music. 'It's part sound, part sophistication – the different time signatures, different harmonies... Maybe not too sophisticated, but sophisticated enough to have some durability. And not too sophisticated to have you just hear it by some piano player in a bar.'

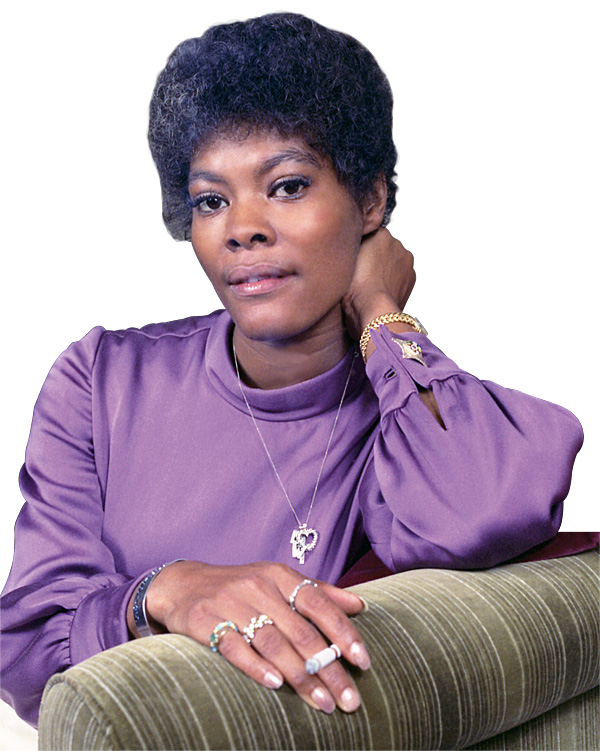

Unlike most other premier producers, he didn't necessarily favour one particular studio over another although he is a creature of habit and feeling comfortable was of primary importance to the creative process. Therefore he usually chose to work in Manhattan where he felt at home and often demo-ed stuff at Associated Studios, with a small rhythm section and a trusted singer, like his muse, Dionne Warwick, who we've already mentioned and who he'd first encountered in August 1961, while rehearsing backing vocals with The Drifters on a song called 'Mexican Divorce'.

Burt was blown away by her abilities, took her under his wing and the partnership would yield no fewer than 15 Top 40 singles in the USA between 1962 and 1968. Bacharach described her voice as having, 'the delicacy and mystery of sailing ships in bottles'.

When it came to recording, Burt would often use the biggest room at Bell Sound, where he'd team up with engineer Eddie Smith, and later at A&R Recording. Hal David remembered these sessions fondly: 'We would start at night and we'd just keep recording. We tried to do two or three songs at every session, and they were very, very exciting'.

Key Skills

The core group were Russ Savakus on bass, Bill Suyker on guitar, Paul Griffin on keyboards or piano, Gary Chester on drum and George Devens on percussion. 'Not only was I used to them,' said Bacharach, 'but they were used to me. That was really important.'

Crack outfit though they were, they performed best when the boss himself joined them on piano. Studio owner Phil Ramone reckons: 'Something happened when Burt played piano. A lot of times he didn't want to, because he was more interested in making sure the whole arrangement worked. I used to constantly badger him. I said, "The rhythm section comes to life when you're playing", and he'd say, "Well, I don't always play in time". But it wasn't about metronomic feel. It was about a feel! – and God knows he had feel when playing'.

Sometimes he'd play, sometimes he'd leave it to the session player, or players, plural. He loved having a couple of ivory tinklers on hand, one playing high, one playing low, a great big full sound perfect for stereo. Also on most sessions were maybe a dozen strings, all played exquisitely by classically trained musicians who could read Burt's charts.

Horns, too, were of paramount importance, often providing the essential hook and the tenor of the shading with a warm, tight, close feel much like a musical hug. To this end, he'd use timpani and, uniquely, the flugelhorn – a softer sound than the harsher, more strident trumpet. Music as embrace. The end product may have sounded easy with a capital E but the skill needed to deliver that effortlessness was taxing. 'I wasn't listening to Top 40 radio,' Bacharach says. 'I didn't like Bill Haley And The Comets. I didn't like rock 'n' roll per se. It was all a little too simplistic, harmony-wise, and those pure vanilla chords...'

What he chose to listen to was classical stuff such as Stravinsky's Firebird Suite or Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé, which he appreciated for their 'extraordinary richness of harmonies'. Most pop songs follow a fairly predictable pattern, and are written in 4/4 time – four beats to a bar – or 3/4 – waltz time. Bacharach wrote in more complex time signatures – 'non-symmetrical phrasing', is how he describes it. Frank Sinatra once joked that Burt 'writes in hat sizes. Seven and three-fourths'.

On the classic recordings, Hal David would also be present in the studio, adding a more holistic perspective to Burt's hands-on approach, hearing the song the way the listener or audience would, husbanding the whole picture. Which was just as well because a perfectionist like Burt, left entirely to his own devices, was prone to occasionally losing perspective.

Take Four

By his own estimate, in the 1960s, between the writing, the arranging and producing, he would probably listen to any single song close to a thousand times. 'And I was still never satisfied with the way it sounded on the radio,' he confessed.

'Because it is a short form; and if it's a short form then make it as good as you can. Because it all counts. There is no filler in a three-and-a-half-minute song.'

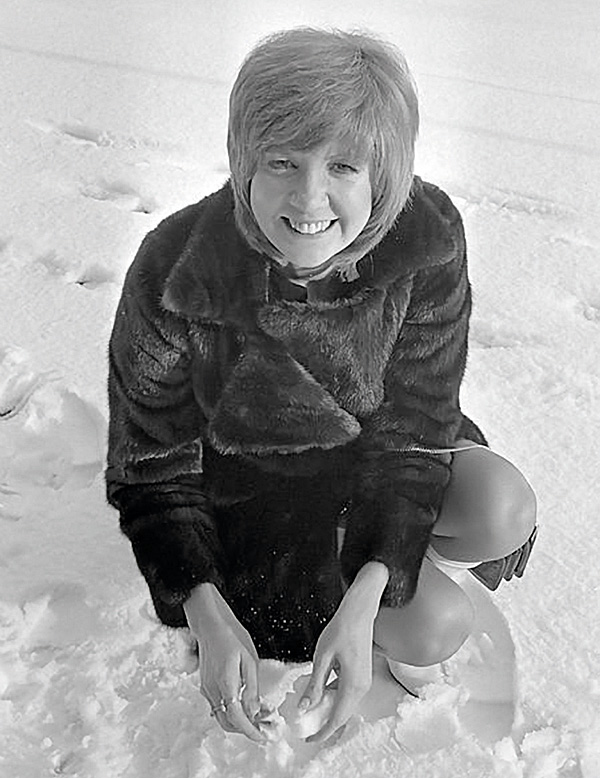

Cilla Black recalled that the recording of 'Alfie', which Bacharach orchestrated and supervised, took 28 or 29 takes as he searched for, 'that little bit of magic'. Finally, George Martin – who was nominally producing the recording session – turned to Bacharach and murmured, 'Burt, I think you got it in take four'.