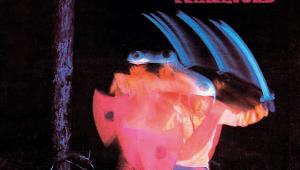

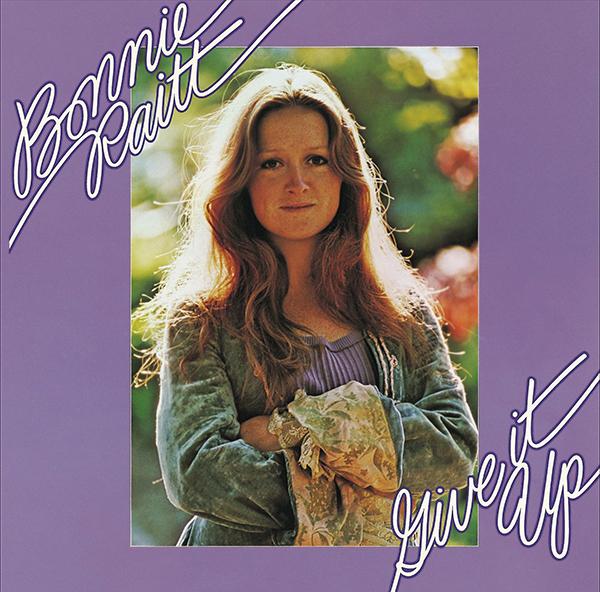

Bonnie Raitt Give It Up

In 1972, Bonnie Raitt told Joe Selvin of the San Francisco Chronicle that she didn’t want to be a star. ‘The music business works to make you a star and I don’t want any part of that. I’ve seen the whole trip’. It was a theme she would return to in interviews, deeming stardom as ‘superfluous’ and having no interest in ‘the cult of personality’ that builds up around musicians. Instead, she enjoyed playing smaller venues so audiences could connect with her as they would do a friend.

Teenage dream

Raitt was born in Burbank, California, the daughter of Marjorie Haydock, a pianist, and John Raitt, an actor and singer, whose Broadway roles included starring in the musicals Oklahoma!, Carousel, and The Pajama Game. This necessitated a move to the East Coast, but the family returned to California and Raitt was raised in Los Angeles, a place she later said she ‘hated’. She was given her first guitar, a Stella model, when she was eight.

California in the early 1960s was synonymous with The Beach Boys and surf music, but as she was moving into her teens, Raitt’s interests lay elsewhere. She told music journalist John Tobler in 1977, ‘I just didn’t like it, I liked soul music. And it didn’t seem such a far jump for me from liking The Temptations to liking Muddy Waters’.

Blues and folk musicians such as Jimmy Reed, Ike & Tina Turner and Odetta were early inspirations. Raitt developed her skills as a guitarist at summer camp and at 15 experienced an epiphany when she received Blues At Newport 1963 as a Christmas present. It comprised recordings of artists who had played at that year’s Newport Folk Festival, including Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, Mississippi John Hurt, John Lee Hooker and Rev Gary Davis.

Raitt has admitted that she might have romanticised these African-American musicians, but loved the mournfulness, pain and sadness in their voices. She found Brownie McGhee’s guitar playing inspirational and John Hammond was the first slide guitarist she’d ever heard. And the fact the latter was white encouraged Raitt to think it was something she could do herself.

Books to blues

She had no particular designs on making it in the music business at this point, however, and in 1967 moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts to attend Radcliffe College at Harvard University, where she studied Social Relations and African Studies. Before dropping out in 1969, Raitt enjoyed being among the ‘Folkies and the anti-war and civil rights movements’ and started to play in local clubs, where she felt she could do better than some of the ‘really bad’ acts that she saw.

Raitt’s reputation as a blues singer – and particularly a slide guitarist – began to grow, and by 1970 she had decamped to New York, opening for John Hammond at the Gaslight Cafe, a venue that had helped launch the careers of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell.

Women singers and musicians had played an important role in early 20th century blues – Chippie Hill, Sippie Wallace, Victoria Spivey and Bessie Smith were among those active before World War Two – but by the early ’70s there were far fewer.

‘I just had a career dumped in my lap. I fill a vacuum – there aren’t any chicks singing blues’, Raitt said. This lack of peers might explain why some felt she could fill the gap left by Janis Joplin, despite being a talented guitarist with a quite different vocal approach.

Raitt landed a deal with Warner Brothers and recorded her debut album, Bonnie Raitt, in 1971. Produced by Willie Murphy, it mostly consisted of covers of songs by writers and artists as diverse as Stephen Stills, Robert Johnson, Sippie Wallace, and The Marvelletes. Yet Raitt contributed a couple of excellent self-penned numbers, particularly ‘Thank You’, a soul-influenced song with flute. The album sold modestly but was critically well received.

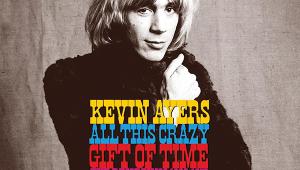

Give It Up (1972) carried on in a similar musical vein, but was more ambitious, with more depth and polish than Raitt’s spontaneous, live-sounding debut. Her singing had grown in confidence and the arrangements had become more imaginative.

Raitt’s great

Opening track ‘Give It Up Or Let Me Go’ features Raitt’s dextrous slide playing on National Steel guitar and has a feel of Dixieland jazz, with bass player Freebo playing tuba, and a deftly arranged, albeit raucous, brass section with solo clarinet. ‘Nothing Seems To Matter’ is folk-inflected with sweet acoustic guitar chord-work and finger picking, double bass, congas and sax. Raitt also delivers a compelling version of the classic ‘If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody’ and recorded her first Jackson Browne song, ‘Under The Falling Sky’. Then Sippie Wallace’s ‘You Got To Know How’ is played as a jazzy ragtime, with the delicious lyrics finding the singer chiding a would-be lover with ‘Don’t try to drink me into bed’.

Released when Raitt was 22, Give It Up only reached No 138 in the Billboard charts, but its original mix of funky, folky, jazzy blues has endured and it’s now considered to be one of her most successful albums. Contemporary critics liked it too. Loraine Alterman’s New York Times review stated that Raitt ‘Plays a mean guitar and [...] has the style and originality that could make her the premier female vocalist of today’s rock’.

American critic Robert Christgau was moved to write: ‘Raitt’s laid-back style (shades of John Hurt and John Hammond, touches of Aretha Franklin and Bessie Smith) is unique in its active maturity, intelligence and warmth’.

Tour of duty

When Raitt’s profile became higher, she toured with blues artists. She saw this as a political statement, but didn’t equate being political to writing songs like a ‘s***ty Dylan’. As she explained to journalist Dave Rensin in 1973: ‘My politics is not which organisation I belong to, it’s how I deal with the people on the street and myself. It’s putting old blues musicians on my bill because they need the work. Having them with me is educational, it shows audiences the real thing still exists’.

These ‘old blues musicians’ included Sippie Wallace, who Raitt lured out of retirement to sing with her at the Ann Arbor Blues And Jazz Festival in 1972, as well as Buddy Guy, Big Boy Arthur Crudup, Junior Wells and John Lee Hooker. Her manager Dick Waterman, in an interview with Rolling Stone magazine in 1975, said these blues originals regarded her as a genuine peer. ‘Not “she plays good for a white person or a girl”, but “she plays good”’.

Raitt was also politically active as a civil rights campaigner, supporting Native American and women’s rights, and went on to perform at high-profile charity concerts, such as the 1979 anti-nuclear benefit sponsored by Musicians United for Safe Energy, an organisation she co-founded. Throughout her 50-plus-year career she’s continued to campaign for sustainable energy and environmental protection issues.

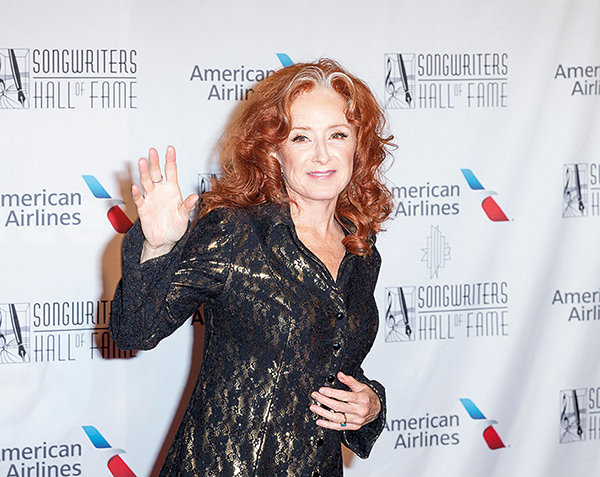

Give It Up eventually reached gold certification in 1985, four years before her commercial success peaked in 1989 with the Don Was-produced Nick Of Time, which marked her first chart appearance since Give It Up 17 years earlier. Nick Of Time topped the US Billboard chart, sold five million copies and began a run of consecutive Top 20 spots up to her 2016 album Dig It Up.

Into the unknown

Raitt has won 13 Grammy awards from 30 nominations, most recently in 2023, when she beat Harry Styles, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift and Adele to win best song with ‘Just Like That’. In an online report of the event The Daily Mail referred to Raitt as an ‘unknown blues singer’. She’d never wanted to be a star, but could be forgiven if she felt rather undersold by that description...