Hyde Street Studios

During my late teens in the mid 1970s, whenever I browsed through the stock in a record shop, if I came upon an album produced at Wally Heider Studios, no matter who it was by, I was more than likely to buy it. Such was the quality guaranteed by the Wally Heider brand that the studio became a kind of shrine to me, a far-off holy grail that shone in my imagination as did that holiest of live venues, the Fillmore West.

Wally Heider – it wasn't just the sound of the records, though that was indisputably great. It was kind of everything. The name had a cool Western allure, like a member of Sam Peckinpah's Wild Bunch or something. And it was what the studio and the records it produced stood for – both an ethos and a soundtrack to an era. This was the place where recordings weren't just made, it's where they were created, where they happened.

The way local San Franciscan musicians gathered together in a community, playing on each other's tracks, making it up on the spot most of the time as they were largely too out-of-it to have anything too pre-planned, this was music that let its freak flag truly fly.

Road To Monterey

Accidents would happen – lucky accidents that were kept on rolling tape, adding to the feeling these were once-in-a-lifetime, never-to-be-repeated performances captured to our good fortune for posterity.

The Grateful Dead; Jefferson Airplane; Quicksilver Messenger Service; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; New Riders Of The Purple Sage... This was the Haight Ashbury crowd at their freewheeling zenith, jamming, experimenting, reaching out to the cosmos, ever searching...

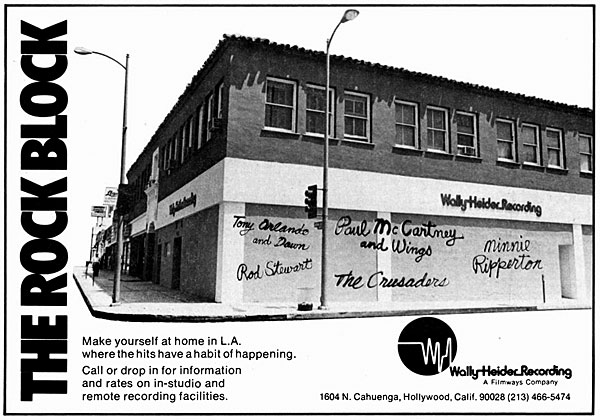

The studio's founder, Wally Heider, had started work in the industry as an engineer at Bill Putnam's United Western Recorders Studio in Hollywood in the early 1960s, after which he founded his own Wally Heider Recording at 1604 N. Cahuenga Boulevard where bands such as The Beach Boys waxed lyrical about the top-notch facilities.

In '67 Heider assisted in the live recording of the Monterey Pop Festival where he witnessed the up-and-coming artists based in the Bay area who, having started their careers having to travel to New York or LA to record, were lacking a suitable facility somewhere closer to home. Heider followed his instincts and, in the spring of 1969, opened Wally Heider Studios at 245 Hyde Street in San Francisco's downbeat Tenderloin district.

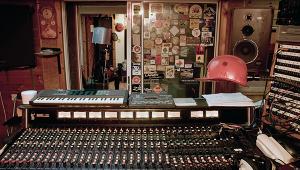

Mcintosh Amps

The building had previously been used by 20th Century Fox to house offices, screening rooms and storage. It's said Heider envisaged four studios on the premises – A and B on the ground floor and C and D upstairs, but Studio B was never finished and instead became a games room. Studio C's dimensions were similar to Heider's Studio 3 in Hollywood though its control room, instead of being at the end the space, was parallel to Studio C's long side. The walls were kept from being parallel with square gypsum devices that were used as midrange sound diffusers and absorbers.

The studios were equipped by Frank DeMedio, who designed the 24-channel mixing console and an eight-channel monitor and cue using Universal Audio (UA) console components, military-grade switches and level controls, and a simple audio path that used one preamp for everything in a channel. Monitor speakers were Altec 604-Es with McIntosh 275 tube power amps.

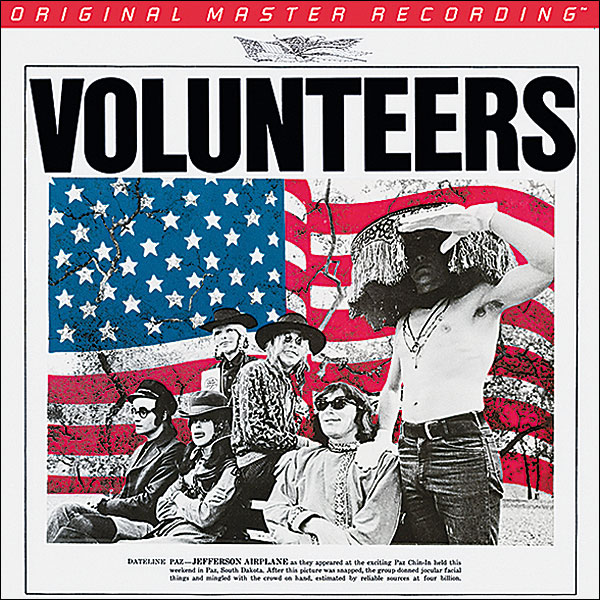

The first record released out of Studio C was Jefferson Airplane's Volunteers and the list of what followed over the next half a dozen years or so reads like a who's who of legendary West Coast recordings. Take a look at this small sample: Neil Young did his eponymous debut solo album there and followed it up with the Crazy Horse-assisted Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young cobbled together Deja Vu here, David Crosby recorded his wonderful If I Could Only Remember My Name (the peak of fellow artist participation which Crosby called 'cross pollination') while Graham Nash did his Songs For Beginners.