Mitsuko Uchida

After Mozart, Debussy. But what of the pianists' long term plans? A psychology of recording by Christopher Breunig

After Mozart, Debussy. But what of the pianists' long term plans? A psychology of recording by Christopher Breunig

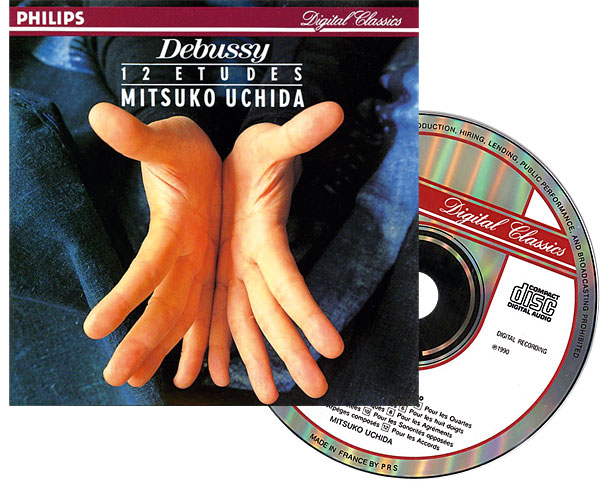

Afavourable acoustic, and music Mitsuko Uchida has been playing since she was 13 years old – but even at The Maltings, Snape, there were unforeseen snags when it came to recording Debussy's 12 Études.

'The wind howls there, you see, and there are aeroplanes – RAF aeroplanes training, and so on. If the weather is filthy they don't fly, but if the weather is filthy there would also be a howling wind. We almost lost a whole day, because in Debussy there are so many pianissimos.

The recording followed a Queen Elizabeth Hall recital in April '89, and Uchida had programmed the studies in Austria, Holland and Germany.

'There's one aspect of my technique that suits Debussy's music: which is lightness, fastness, and flexibility. And when you have this it is a first step to a certain natural playing of Debussy. Flexibility and lightness doesn't help at all playing Beethoven – then I really have to work hard on the sound.

'At first, you don't think they are that difficult – I started playing the Études when I found everything difficult. I didn't see any difference between the difficulty of the Debussy and the difficulty of a Mozart sonata. Later on I thought "oh, they are okay" – but when it came to the crunch, God was it very hard! Because, compared with the Préludes, the extent of concentration is incomparably higher. The tightness of every event is quite stunning. After having recorded the Études, and doing a TV version of it, I came home and sat down, played the Préludes, and thought "I must have been mad…".'

Was it your suggestion to Philips? Because they are not that common.

'That is why I wanted to do it. Especially at a concert, hardly anyone plays all 12 in one go. As a set, yes, a few in combination with other things. But I believe in a group to be looked at as a group. That conviction I got probably when I played the Mozart sonatas for the first time, complete, in public. You have a totally different vision and experience of the whole thing.

But what did you think, hearing them as a listener?

It wasn't difficult to come to them as a listener because there is so much life, such funny moments here and there, so much imagination – flights of imagination – and strange visions. It's like looking at – what do you call that thing? A kaleidoscope.

'Yes, I can go on for ever! There is nothing monotonous about them being études, not at all. Whatever technical purpose the composer might have had, no music should ever sound [difficult]. It is, utterly, my personal problem if I am playing: I should present it at a stage when it feels easy, looks easy. Even when I am suffering, no-one should know. That is something I believe in, and "wow" was it tough!'

Can we jump to the television programmes you did on Mozart, with Jeffrey Tate? Was the first – on the C major Sonata – improvised, or scripted?

'Both programmes where I was participating there was no script. For the solo I devised, like, a sonata form, a structure, what I had to say. I had worked out vaguely how long each section might take, thought about it a lot, and then "bang!" off we go. They just needed to splice out a few mispronunciations.'

Did they try to dissuade you from discussing subdominants? After all, your talk was quite technical

'It was quite a struggle in that first place to get that little sonata to be accepted: everybody wanted something more obviously dramatic, like the A-minor. The little C major fitted my scheme very well, because it was so concentrated, but concise. lf I had started off on the C-minor Fantasia and the Sonata I would be talking very vague stuff, the mystery of Mozart, without the details.'

Would you like to do more?

'I'd love to. I did a fairly conversational piece for German television on the Debussy Études – 20 minutes of talk. The producer threw ideas, questions at me. The only condition was that whatever I said I would have to produce on the piano. Somehow I didn't take it in clearly, and I said "after Wagner's chromaticism Schoenberg was inevitable", and he said "Show me some Wagner". Ach! Tristan und Isolde, or something like that. We talked about concepts: what Debussy did, what his special way of thinking was – how he established his own clear language.'

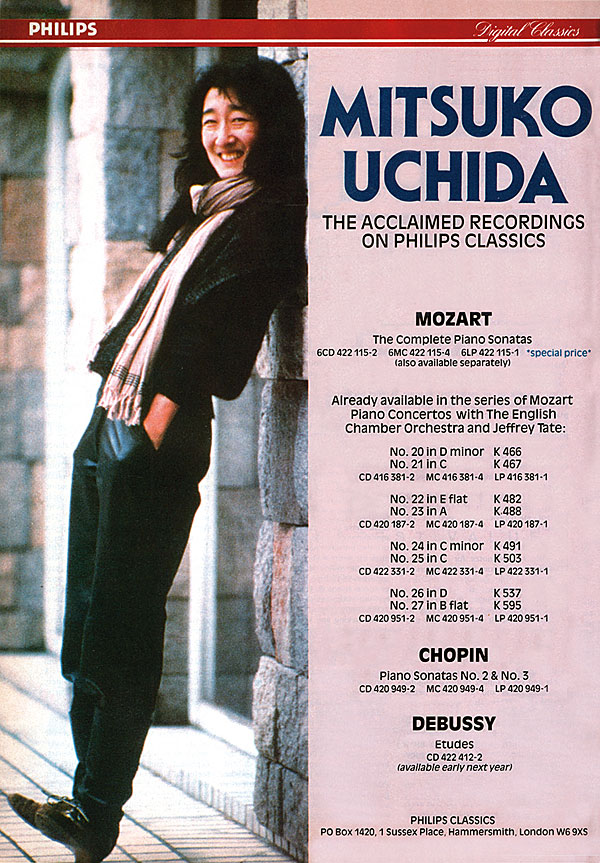

So, what comes next?

'I don't know what to bring out now because, from my Mozart experience, I am convinced should I ever record Schubert sonatas, which I would love – it has been my greatest love – I shall do so only when I have been playing them as a set. It is different from studying them, or playing them in public one by one. It will take a long time.'

So will you give cycles in concerts, then?

'That would be in the not too near future. I am planning to do, for instance, some lmpromptus in concerts, and if they are ready I might record them. Or I might have a group of late Chopin pieces, including the Polonaise-Fantasie. They are wonderful pieces: the Barcarolle, Berceuse, some of the late Nocturnes or late Mazurkas maybe.

'But I was thinking in terms of Schubert and Beethoven. I shall take a lot of time: five years, if I am lucky. Beethoven: the concertos are coming up in concerts. In terms of solo music I might, in secret, try out the Diabelli Variations in a couple of years. So I shall build up a Beethoven repertoire, thinking of him in terms of ten years or so.

'And in between I think I shall pick up everything, and do probably quite a lot of 20th-century music, including Debussy, Bartók, Schoenberg – definitely Schoenberg. I adore the Concerto! I hope I shall have it ready for recording in the not too distant future; but the difficulty is what to combine it with. Alban Berg: there is the Sonata, and the Chamber Concerto. That is definitely on the agenda. Webern I play anyway. And... sneak in some 20th-century music that people don't know, or people wouldn't recognise, as encore pieces.'