Star Potential Page 2

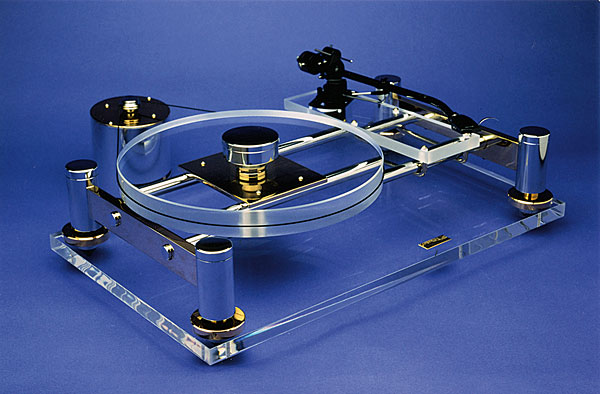

Let's not mince words here: I haven't seen such erratic behaviour from a simple round cross-section 'rubber band' since the days of the unlamented Oak. No matter what I tried, it would ride up and down the sides of the platter. I did everything I could to ameliorate its wanderlust, especially setting the motor assembly at different heights, a millimetre at a time, to exploit different areas of the 30mm thick platter's vertical surface. Dead centre, riding near the top, riding near the lower edge – nothing would alter its aberrant behaviour.

Did it matter? Given that two strobe discs showed sublime speed stability, and that material with a particular vulnerability to wow and flutter revealed no sonic weaknesses from the Quasar in this department, it's certainly arguable that unstable, 'unhorizontal' behaviour from a belt may cause no ill effects. On the other hand, if something should look right to be right, then the quivery Quasar belt compromises the deck's glorious styling in the way that a sore on her upper lip would kind of ruin a Vogue cover shot of the truly perfect Linda Evangelista.

The cure? Simple: the platter on the Quasar should wear a groove around its circumference (two grooves, actually, to accommodate both speeds) to 'capture' the current choice of belt. Either that, or the company should try a different pulley which accepts flat cross-section belts. Savic didn't go into denial mode or start calling me 'anal', but I must admit that his relative lack of concern about this worried me as much as the belt's erratic movement.

![]() Sound Quality

Sound Quality

But enough bitching: this deck is one sweet-sounding, coherent, dynamic performer. With the luscious Helius tonearm in place, and Savic's Goldring replaced with a Lyra Clavis for the listening sessions, I fed the Quasar front-end into a Trilogy 905 head-amp, the GRAAFiti WFB TWO preamp, GRAAFiti 5050 power amplifier and Quad ESL63 loudspeakers. Music? Lots of singles, especially a delightfully scratchy copy of Bud Flanagan's 'Who Do You Think You're Kidding, Mr Hitler?', a bunch of recent Mobile Fidelity Anadisc 200s, the awesome Best Of Gilbert & Sullivan 3LP box set from Reader's Digest (circa 1963, stereo, mint and secured for a fiver on holiday in Torquay... which speaks volumes for visiting Torquay), and anything else in reach. In fact, couldn't stop.

Talk about more-ish. The Quasar, although probably the quietest deck I've heard this side of £2000, approaches the conundrum of playing LPs in the digital era by using a rather different approach than, say, the Michell decks, SMEs or Max Townshend's stunning Rock and its derivatives. These turntables, to elicit a groan, turn the tables on CD by being just as clean and precise as digit-heads expect CD but not LP to be, and they do it without forsaking the glories of analogue.

The Quasar doesn't even attempt to emulate those turntables with their near-laboratory-standard behaviour. Instead, the Quasar uses its quietness more as proof that LPs needn't seem to throw out higher noise floors than CDs rather than to suggest that LPs are actually as quiet as CDs. (Which they emphatically are not. Don't you just love 'denial'? And how some analogue champions swear blindly, or deafly, that LPs are as quiet as digital formats? I suppose they are, when they're not rotating.)

So, working from a position neither of defensiveness nor of digit-envy but of confidence in its medium, the Quasar simply revels in 'analogueness'. It's lush, it's fat, it's warm, it's involving. Even squeaky- clean, modern LPs taken from digital originals sounded more ear-friendly than their CD equivalents.

There's something about the Quasar turntable that suggests 'middle ground', moderation and tranquillity. The soundstage, while as precise and three-dimensional as is required, is not as Cinemascopically grand as that of the Michell GyroDec. Bass is extended and controlled, but less tightly damped than that of the Garrard 401. Treble? It's sweet as sugar, but without the ultimate attack. And still the Quasar represents a sane approach to analogue playback which will satisfy an LP-playing hard-core, while not alienating those who listen to CD.

Conclusion

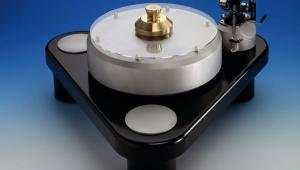

Perceived value? This turntable is an absolute bargain, especially if you never expected to have a piece of sculpture thrown in for free. It looks as clean and modern (and therefore ironic) as did the Transcriptor deck [HFN May '11] that the character Alex used in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 masterpiece A Clockwork Orange. But, please, Savic, do something about that belt...