For the record

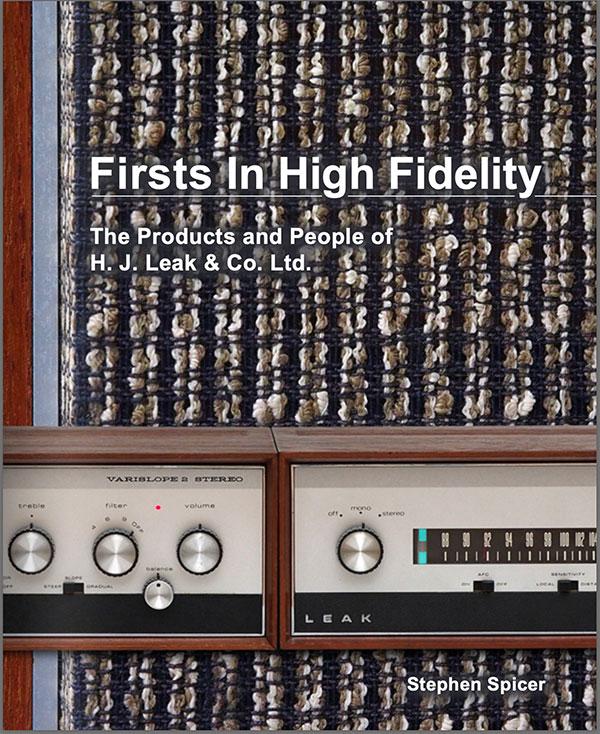

I was recently delighted and excited to hear that a new edition of Stephen Spicer’s book on the history of Leak – Firsts In High Fidelity – has been released. The original edition appeared as a large-format paperback in the year 2000, and it’s a fascinating account of the story of the people involved, the company, and its products.

It’s therefore a wonderful collection of information for anyone interested in the history of ‘classic’ top-grade British hi-fi equipment. Though it was a shame that photographs and circuit diagrams included in the 2000 edition were printed in monochrome so could not show the true appearance of the equipment, or indeed, the people and places.

Coffee Table Tome

Unfortunately, the original publisher shut down, consigning the copyright situation – and hence the prospect of any new edition – into limbo. However, Spicer has now been able to get a much bigger, better version published. This is a superb, large-size hardback edition with updated and increased content, and with many colour illustrations – a ‘coffee table book’ in terms of its presentation, and with even more information inside. If you want to know more about the history of British hi-fi, I’d argue it’s essential reading.

My experience with valve-era Leak products was mainly with the company’s Troughline FM tuners. I thought its approach was ingenious and – for the time – delivered excellent results. However, these models were designed during a period when the UK’s Band II FM spectrum was only occupied by a smattering of BBC ‘National’ stations along with some ‘Police’ comms at the top end of the band. As a result, the tuners could employ a wide IF bandwidth to deliver low distortion, etc, making them ideal for mono transmissions that weren’t cramped by many other stations in the adjacent channels.

Alas, first ‘stereo’ arrived, and then many local stations – commercial as well as BBC. This meant that a much tighter bandwidth was often required to avoid interference, while needing a wide bandwidth for good stereo. This is a combination of demands that has challenged FM radio designers ever since. In such an environment, older mono-era tuners struggled to deliver their original quality of audio output. Eventually that led to Japanese ‘supertuners’ displacing Leak’s early designs. Leak’s ‘Stereofetic’ then struggled to compete.

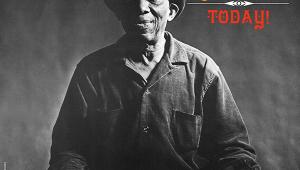

Harold Leak, who founded the company in 1934, is pictured in an ad for the Stereo 30 amplifier, launched back in 1964

Gone But Not Forgotten

Although we can now welcome this book, it remains frustrating that ‘serious’ historians (ie, academics or museum curators who are, unfortunately, often clueless about engineering, manufacturing, or ‘domestic’ audio) continue to largely ignore hi-fi. The impression given is that in some odd way they take for granted that hi-fi isn’t really a part of history or sociology, or matters in any way. It’s not a ‘respectable’ subject for historians, curators, or researchers at our established institutions.

As a result, collecting, preserving, collating, and presenting this information gets left to enthusiasts as a sort of obscure ‘amateur’ history area. That in turn can all too easily lead to information being lost when the people who worked in this area or lovingly used their products pass away. And if that continues, no-one later will ever fully realise just how much noteworthy history may have been lost.

A Call To Arms

Hence for more reasons than one, we need more books like Spicer’s on the various designers, manufacturers and engineers, as well as the kit they made and sold. More people need to decide they’ll write a book on an aspect of British audio (or American, if you’re reading this from across the Pond). As it is, we can only be thankful that someone in Australia has put so much work into producing a superb book on a notable British audio marque.