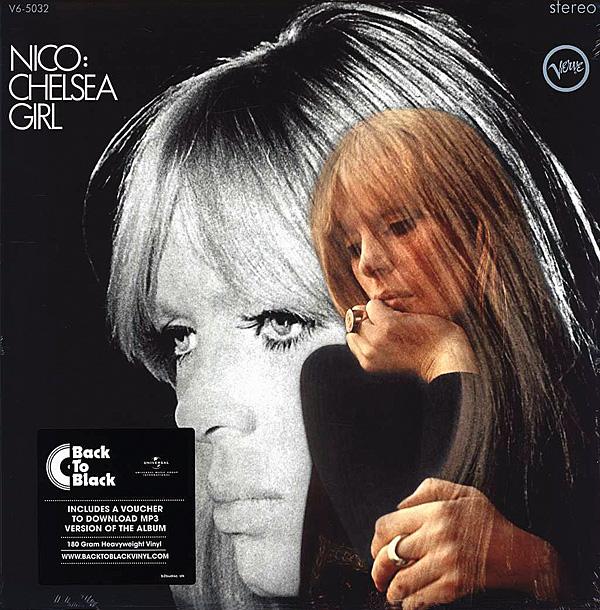

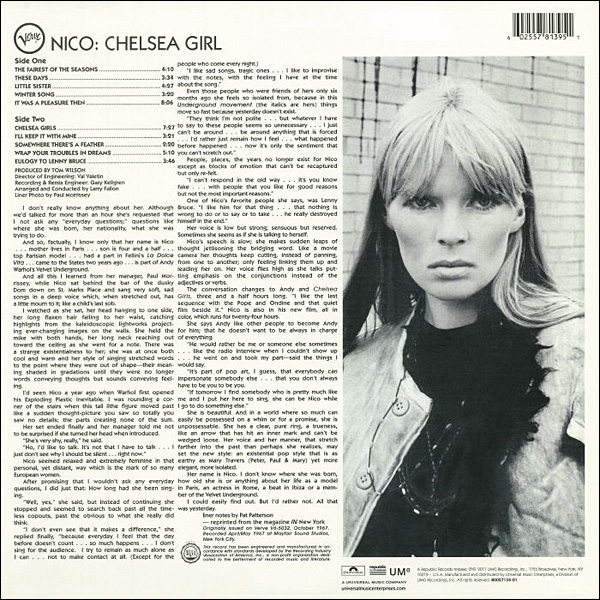

Nico: Chelsea Girl

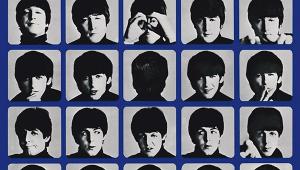

'The first time I heard the album, I cried.' It's rare but not entirely unknown for a musician to disown their own work. Lee Mavers wanted nothing to do with his one and only La's LP [HFN Nov '17], claiming the finished article did not represent the melodic visions gambolling in his brain. And Paul McCartney famously baulked at all the lush orchestration Phil Spector lavished on The Beatles' Let It Be.

Wishes Ignored

But Nico really, really loathed her 1967 debut solo album Chelsea Girl. 'I still cannot listen to it,' she complained some years later, 'because everything I wanted for that record, they took it away. I asked for drums, they said no. I asked for more guitars, they said no. And I asked for simplicity and they covered it in flutes! They added strings and I didn't like them…'

What all three of these artists have in common – apart from their abject dismay – is, of course, that they're wrong. The La's 'There She Goes' is indie genius, 'The Long And Winding Road' is in no way diminished by Phil Spector's somewhat heavy hand, and Chelsea Girl, no matter what Nico thought, is downright gorgeous.

Her predicament was simply that, as a woman in a man's world, she was up against people who insisted they knew best and weren't inclined to take on board her point of view. The 'They' she refers to is essentially its producer Tom Wilson, a man with an admirable track record and a stubborn propensity for embellishment.

It was Wilson, working on 'Like A Rolling Stone', who coaxed Bob Dylan away from his folkie roots in an anarchic electric rock direction. It was Wilson, too, who virtually created Simon & Garfunkel. The duo had split after the commercial failure of their 1964 debut LP, Wednesday Morning, 3AM, but, unbeknownst to them, Wilson, who'd produced the album, overdubbed electric instrumentation onto the 'Sounds Of Silence' single and within a few months it was No 1 in the charts.

So he was up to his old tricks again when it came to Chelsea Girl. Wilson had first encountered Nico during the recording of The Velvet Underground's debut LP. Although the sleeve says that Andy Warhol produced it, it was really Wilson who was responsible for helming The Velvet Underground & Nico, a project over which the singer had absolutely no say.

Where she'd come from was somewhat of a mystery. She was German to be sure, there was no mistaking her heavy accent, but a lifetime apparent need to self-mythologise muddied the already dark waters. She was born Christa Päffgen in Köln in 1938 and at 16 was modelling around Europe, taking the name Nico from an ex-boyfriend, photographer Nikos Paptakis.

In 1959 she had a minor acting role in Fellini's La Dolce Vita and was studying acting in New York under Lee Strasberg. She'd actually released a single before being hooked up with The Velvets. Coming to London she recorded a decent Gordon Lightfoot song, 'I'm Not Sayin'' in the manner of Marianne Faithfull, for the Immediate label. Her boyfriend at the time, The Rolling Stones' Brian Jones, produced.

Hooking Up With Warhol

Once back in New York, it was surely inevitable that she'd hook up with Andy Warhol's glamorously dissolute crowd at The Factory. Warhol had recently been approached to help open a discothèque in Long Island and was looking for a house band. Coincidentally, he had just encountered The Velvets at the Greenwich Village venue 'Café Bizarre' and decided that they fit the bill, insisting that they take on Nico as window dressing. 'Something beautiful to counteract the kind of screeching ugliness they were trying to sell,' explained Paul Morrissey, a Factory filmmaker and one of the band's first managers. 'And the combination of a really beautiful girl standing in front of all this decadence was what was needed.'

The band's leader and centre of attention Lou Reed was not a happy bunny but he sucked it up – the Warhol connection was too good a main chance to pass up over a hissy fit. Apart from the fact that Nico was likely to steal Reed's spotlight, there were three further complications: she was supposedly deaf in one ear so couldn't sing in tune; she thought of the band as her backing group and wanted to sing every song; and the band didn't actually have anything in their repertoire she could sing. Reluctantly, on Warhol's insistence, Reed wrote her a trilogy of ballads that now stand as some of the most haunting ever.

In a precursor to the material that would emerge on Chelsea Girl, 'Femme Fatale', 'All Tomorrow's Parties' and 'I'll Be Your Mirror' seem, as one astute critic put it, 'directly drawn from Nico's psyche'. This was the scenario that Tom Wilson inherited, so when he was presented with the task of producing her solo debut, maybe it's little wonder that he rode roughshod over Nico's wishes.

Nico began a solo residency at a club called 'The Dom' in St Marks Street where she was initially accompanied by a tape deck playing Reed's pre-recorded guitar solos, an engagement that led to guests dropping by to help out – including Reed, The Velvets' John Cale and Sterling Morrison, local hotshot Tim Buckley, Tim Hardin, Leonard Cohen and a talented young waif called Jackson Browne (later her lover). When The Velvets had an offer to tour, Nico stayed in New York.

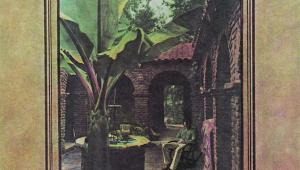

Inspired by her then lover, The Doors' Jim Morrison, to make a record of her dreams, what she did instead of touring was Chelsea Girl. Recorded at Manhattan's Mayfair Studios in October 1967, the album was named after Warhol's 1966 experimental documentary Chelsea Girls in which Nico starred. It captured the mundane day-to-day activities of scenesters at the infamous junkie hang-out The Chelsea Hotel.

Ultimate Loner

Chelsea Girls' title track, written by Reed, is almost a continuation of the film in the form of a ballad, each verse detailing the comings and goings of the hotel's retinue of drag queens and addicts. The ten tracks were all written by the men in Nico's life and, it seems, composed for and about her. 'I'll Keep It With Mine', for instance, was written while Bob Dylan vacationed with Nico in Greece in 1964. Each track is a complete communion between writer and singer, so personal they became hers alone.

The best known track after the title number is Jackson Browne's 'These Days' – 'the ultimate loner anthem'. Many have attempted it over the years, including Browne himself, but no-one comes close to matching Nico's melancholic resignation.

The amazing thing about Chelsea Girls is that, although it was created out of New York decadence, it is timeless, placeless and unique because, quite simply, there was only one Nico and nobody sang – or ever has sung – the way she does. One critic remarked that on the Lou Reed/John Cale collaboration 'Little Sister', she sings like 'a cello getting up in the morning'. And the flute and strings she hated so much? They're moody and magical, arranged by Larry Fallon who wove the same magic on Van Morrison's Astral Weeks.

On its release, Chelsea Girl's reception was lukewarm to say the least, The Los Angeles Times summing it up, 'Nico's a classy girl, but they'd sell more Nico if she were naked – and not hiding behind a string orchestra in a flower print dress'.

How very wrong they were. From then on Nico took complete control of her own destiny and recorded a series of the most extraordinary and bleak albums in the history of rock.