The Land Without Music?

The Land Without Music?

A century-old legend of suspicion and exceptionalism continues to haunt attitudes towards English music, says Peter Quantrill - and it appears that it's the English who won't let it goThe spring cleaning of schedules at BBC Radio 3 took its listeners by surprise, to judge from comments both within and outside the media. The 'shop window' of Record Review on a Saturday morning moved to the first floor, in the afternoon. The spoken-word programmes were shunted off to Radio 4, while Friday Night Is Music Night has resurrected an antique Radio 2 title. The channel's once-serious coverage of new and contemporary music is almost entirely effaced under the controllership of Sam Jackson, who formerly headed up Classic FM.

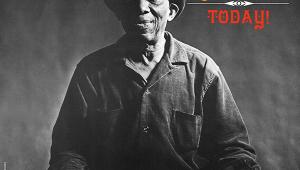

Oskar Winner

It's too soon to say how these changes will affect the character of Radio 3, or (perhaps more crucially, for its continued survival) listener figures. But the Music Matters slot was relaunched in bold fashion with a six-part documentary series, examining the state of music in Britain. Fronted by Richard Morrison, long-time classical critic of The Times, the series tackles the issues head-on, and it's well worth your time (you can find it on BBC Sounds).

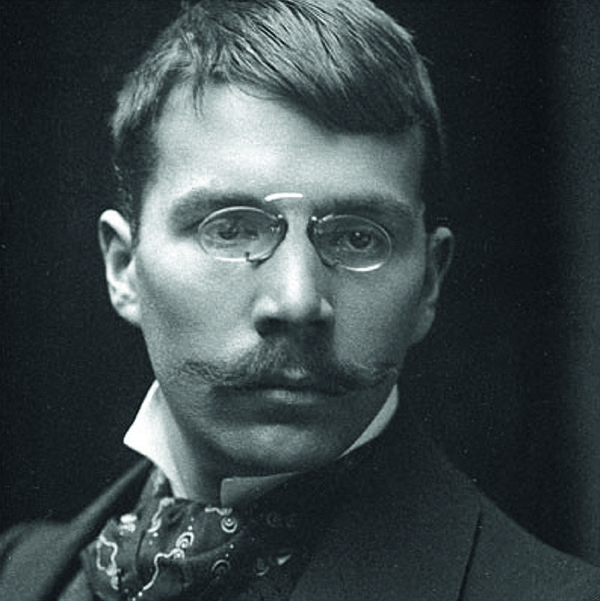

What tweaked my antennae was the series title: The Land Without Music?. This phrase revives one of the oldest, most vexatious clichés in discussing the state of music north of the Channel. Now is not the time to address whether it refers to English or British musical culture. As Morrison reminded us, the phrase was coined by a German journalist, Oskar Schmitz. It forms the title of a pamphlet-length broadside directed more generally at the English, and published in a year, 1914, when Schmitz hardly needed to stoke the fire of Anglophobia among his German readers.

Nonetheless, often mistakenly re-dated to 1904, the insult of 'Das Land Ohne Musik' hit home, and how. Searches of news databases online confirm how perennially it has been revived, both in the original German and in an English translation, and almost exclusively by British writers. I am sure that Schmitz (who died in 1931) would be delighted to find his immortality in the countless spirited defences of Elgar, Vaughan Williams and the rest, which continue to be mounted to this day.

Anyone about to use the phrase should take a step back, and a deep breath. Who is it they think they are talking to? Notwithstanding the slaughter of two world wars, the Germans welcomed English music and musicians well into the 20th century, and do so now more than ever (who was the previous chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic?). That Richard Strauss acclaimed Elgar as his 'highly esteemed friend' is well known; so too the popularity of Gerontius abroad.

More often forgotten is the frequency of Vaughan Williams performances in Germany and Austria. As one representative example, Wilhelm Furtwängler conducted the First Norfolk Rhapsody with the Vienna Philharmonic (in the Musikverein!). Carl Schuricht was a champion of Frederick Delius throughout his career. Italy boasts a long heritage of Elgar performance owing nothing to its émigré son, John Barbirolli, and everything to a natural sympathy with the style of works such as In The South.

Worst Enemies

No: it is the English themselves who still need convincing that Schmitz's barb was no more than a mid-war call to jingoistic pride. 'England is not a musical nation, and never will be. As soon as the country is musical, it will cease to be English.' Schmitz did not say this, nor Theodor W. Adorno: it was Elgar, in 1926.

We shouldn't be surprised. Elgar had enough chips on his shoulder to fill a cone from Mr Chippy. And besides his own lifelong insecurity, he could see that, in 1926, the world centres of musical innovation lay elsewhere, principally in Paris. Times change, and at several points in the last half-century, Britain has produced and exported classical composers and musicians with global reach and influence. If only we weren't our own worst enemies.