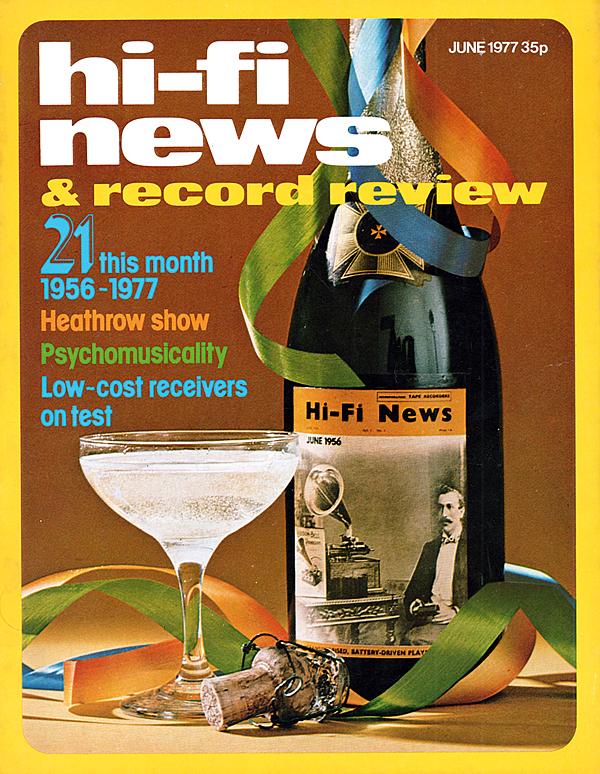

Hi-Fi News: 21 this month, June 1977

John Crabbe, editor of HFN/RR, reflects on two decades of audio advance

John Crabbe, editor of HFN/RR, reflects on two decades of audio advance

The galaxy of experts that were gathered together by Miles Henslow, founder and first editor of HFN, to help fill the pages of his pioneering magazine in 1956 still has a ring of authentic hi-fi quality as it shines across two decades of progress and expansion: Cecil Watts, Ralph West, Gilbert Briggs, Stanley Kelly, James Moir, R S Roberts and H Lewis York.

Then, a little later, these names were joined by G F Dutton, John Borwick, Rex Baldock, B J Webb, George Tillett, J Somerset-Murray, E J Jordan and P J Guy, all of whom played their part in creating an image of accuracy and reliability.

Quality Guaranteed

In his Editorial of June 1956, Vol 1, No 1, Miles explained and justified his use of the hi-fi tag in a magazine title: 'We feel strongly that the term "hi-fi" should be held in respect. lt does not matter much, in itself, if the tag is misused, but it matters a great deal if people are misled by its misuse. Since hi-fi or high fidelity is the term which thousands of people, the world over, have accepted in their minds as a guarantee of quality, in terms of sound recording and reproduction, a high quality label tied on to the wrong piece of baggage can do a lot of harm.

'lt is inevitable that more parcels will be incorrectly labelled, but it is our aim to see that this does not happen in the sorting office of Hi-Fi News. By purposely using "Hi-Fi" in our title, we shall have a constant reminder that we ourselves have a standard to maintain.'

The standard for hi-fi was already very high when Hi-Fi News first appeared; indeed, the cover picture on the second issue was of a Quad/Ferranti system. But equipment of that standard was confined only to a tiny fraction of those who consciously regarded themselves as hi-fi enthusiasts, while the whole band of such hobbyists, extending down to dreamers who simply couldn't afford any more than a corner reflex speaker added to their record players, comprised no more than a drop in the ocean of music-loving domestic consumers.

Miles casually assumed in his first editorial that the term hi-fi was accepted as an 'assurance of quality' by 'thousands of people the world over'. Whether or not the assurance is still as clear in 1977 as it might have seemed in 1956, the number of people owning and using hi-fi equipment around the world has now rocketed up into the millions or tens of millions, while those simply aware of the term must run into hundreds of millions: a revolution in scale, if not performance.

Tinkers 'N' Dabblers

One way of looking at the transition of hi-fi from evolution to revolution is to divide it into five phases. There have always been the technical enthusiasts, and insofar as a hi-fi hobby could be said to have existed before the 1939-45 war, it was the tinkerers and dabblers who kept it going. This can be considered to be phase one. Then, in the immediate post-war period a huge growth in the numbers of men with experience of electronic circuitry joined what were considerable improvements in recorded quality on the 78rpm disc (largely by virtue of Decca's ffrr, developed under Arthur Haddy) to make the home-built amplifier or loudspeaker a more worthwhile project than ever before.

Making Money

This was phase two, and was an exciting time aptly symbolised by the first edition of Gilbert Briggs' Sound Reproduction, published in 1949 and the bible of thousands for a decade or more. And, of course, the name of that great pioneer Paul Voigt linked the pre- and post-war phases by courtesy of Lowther. This period also saw the birth of domestic hi-fi as a viable business activity, with the more entrepreneurial among those post-war technicians using their audio wits to make money as well as reproduce music. Of those who remained hobbyists, some went beyond radios, amplifiers and speakers to tackle pick-ups.

The third phase began with the long-playing microgroove record around 1950. Decca was again the pioneer (in the UK) in providing the software signals to stimulate both hardware experiments and the production of equipment.

As FM radio was not yet known in Britain and tape recording was still a rather awesome new idea, those LP records offered quite the best source of musical sound to be had. Once pick-ups and/or their associated circuitry had been adjusted to allow for the effect of compliance in the vinyl record material (which lowered the HF resonant frequency and made some pick-ups sound very toppy in the early LP days), it rapidly became clear that here was a great new source of sonic pleasure.

More and more enthusiasts built amplifiers based on Wireless World circuits or loudspeakers using the latest combination of Wharfedale or Goodmans drive units, while the annual London exhibition of equipment organised by the British Sound Recording Association was fast changing from a trade display to a public show. Then, in 1956, the BSRA dropped out and we had the first Audio Fair under the impresario Cyril Rex-Hassan and HFN was born.

The scene was set for phase four, primed by the introduction of EMI's superb Stereosonic music tapes in 1955, oiled by a now expanding interest in tape recording and a nascent FM broadcasting system, it launched with the stereo disc in 1958.

Civil Resistance

Stereo on disc had its birth-pangs, of course, and once again it fell to Decca to achieve the first cleanly cut two-channel records. But within a year or so the better issues from all the major companies were very impressive, a growing number of stereo pick-ups and stereo amplifiers of good quality became available, loudspeaker manufacturers started looking seriously at the possibility of exchanging electroacoustic efficiency for reductions in size, and we were on the verge of phase five. But first came a process of conversion, for while the wider public was beginning to show an interest in hi-fi, it had to be moved away from the one-piece player to an acceptance of two speakers separated from the 'works'.

Resistance was as much commercial as domestic in those crucial years. Although the pioneering specialist hi-fi manufacturers were serving a lively and fast growing market, the big traditional manufacturers of radios, record-player/s and TV sets were not convinced that the hi-fi bug could ever bite very deeply over a wide area.

Link House

But they were wrong. Phase five saw the 'big boys' move into hi-fi during the mid 1960s: the low-distortion transistor amplifier started to look viable, what we cheekily called 'chopped up radiograms' proliferated under respectable names like 'unit-audio', separate bits and pieces became acceptable in previously non-hi-fi homes, and we were away!

The age of mass-production hi-fi had come, and small pioneers were in some cases absorbed by giants who knew all about selling to the big general public. The old-style Audio Fair at the Hotel Russell came to an end in 1968, the Japanese started taking an interest, and the present-day hi-fi scene arrived.

When I joined HFN as Technical Editor in 1962 the subject was hovering near the middle of phase four, and it was perhaps symptomatic of the oncoming 'big business' epoch in hi-fi that in 1964 Miles Henslow sold this magazine and its partner Tape Recorder to Link House.