Class Distinction

Ken Kessler goes Class A in a small way with the Marantz PM-4

Ken Kessler goes Class A in a small way with the Marantz PM-4

Phone calls from company spokespersons such as Marantz's Steve Harris, are generally one of two types. Either 'Would you like to review our new Model XYZ whatever?' or 'Where the hell is our Model XYZ whatever, which you've had for nine months?' Such phone calls are never about reviewing components that are out of production.

But I hadn't reckoned on Steve being a latent anachrophile. It seems that my review of the legendary, long out-of-production Marantz Model 7 Preamplifier [HFN Nov '84] affected Steve the way Roots affected half the population of the USA, and it must have awakened in him an interest in his employer's past. But knowing Steve, there had to be an ulterior motive, the cynic in me refusing to accept the notion that he'd found a Marantz Model 10B tuner or some equally desirable antique. I was right.

Success Story

Rather than undermine my genuine love for the Marantz PM-4 by giving you the impression that I'm reassessing it for the wrong reasons, I'll save that bit until the end. Nobody has to twist my arm to get me to write about products this good. What baffled me was editor John 'Pops' Atkinson's willingness to place an item into the magazine's 'Anachrophile' column when it only ceased production a year ago.

The PM-4 justifies itself by having been years ahead of its time. Ask yourself, 'What's the biggest success story of the past 18 months?'. Unless you're one of its competitors, you'll immediately say the Krell KSA series. And what's one of the main reasons for the good sound? The Krell amps are pure, genuine Class A designs. And Class A operation means no crossover distortion from the active devices as they operate all the time, instead of switching on and off as with the more economical Class B.

True Wizards

The trade-off, alas, is in the area of efficiency, for Class A amplifiers waste a lot of energy through heat. Affordable ones tend to be low-powered while truly usable ones with in excess of 50W generally cost a bundle. Class A amplifiers came back into fashion in the mid 1970s, by way of approved high-end makes such as Electrocompaniet and Mark Levinson. Some Japanese companies then jumped on the bandwagon and cooked up all sorts of bogus, pseudo-Class A formulae in the hopes the legend 'Class A' – regardless of prefix – would fool the consumer into thinking they could get Sugden or Electrocompaniet or Levinson sonics for £119.

Marantz, too, entered the Class A sweepstakes, but not with some marketing expert's concept of what that label means. It would appear that someone in Marantz realised that their name once stood for the highest of the high-end, and that a Marantz badge should signify more than your basic Japanese marketing chicanery. And bearing in mind that Marantz has in its employ true wizards like the inimitable Ken lshiwata, such a project was far from being a mere pipe dream.

Dirt Cheap

The return to former glory manifested itself as the Esotec series, and readers with decent memories will recall that even some British reviewers gave the Esotec Class A amps their nods of approval. The company earned kudos by offering the Real McCoy, and it paid off; they suffered none of the sniggers that greeted 'Super-Duper Long-Life UHT Class A' or 'Semi Transparent Simulated Class A'. The MA-5 and SM-6 amps were worthy of the name Marantz in a way that nobody could have expected.

While the Esotecs were bargains by Levinson or Krell standards, they still cost more than the average consumer could afford, and it meant that Class A remained out of reach of the majority of shoppers. But Marantz had a gift up its sleeve for the less well-heeled. In January 1980 it unveiled an integrated amplifier with real Class A operation, and it only cost £299.

'Only' is a relative term, and I know that there are people who consider even £299 a vast sum. But the relativity also applies to its cost in comparison with other amps of its type, not just with the size of people's bank accounts. And £299 was – and still is – dirt cheap for a true Class A amplifier, let alone one with a comprehensive preamp included in the price.

Unfortunately, too many people are still suckered by specifications. When a salesman tells a customer that his £299 is paying for 15W per channel – even after explaining that 15W of Class A isn't quite the same as 15W of anything else – the typical reaction is to look at other products. If only they'd listen, both to the salesman and the amplifier... For starters, a switch turns the Marantz PM-4 into a creditable 60W amp of Class AB persuasion. In that mode, it was no better or worse than anything else that the Japanese were selling for £299. But run the little devil in Class A, with loudspeakers of a not-too-hungry nature, and there was a taste of high-end magic at a low-to-mid price.

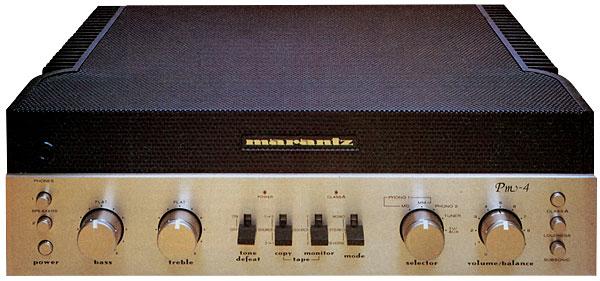

As for the amplifier's perceived value, which seems to be the initial motivation in spite of exhortations from the press to listen to gear rather than look at it, the PM-4 was a winner, though many showed the bad form of disliking its fresh – indeed, gorgeous – looks. Perhaps it had been too many years since the valve heyday, when a shiny fascia might be topped by a mesh cover. I've always liked the champagne finish of Marantz equipment, and I like the graphics which so many find objectionable. And the black-over-gold is icing on the cake.

Money's Worth

Styling, though, is too subjective an area for me to get dogmatic about, so let me carry on the perceived value angle with a different approach. On a most basic level the size and weight tell the consumer that he's getting his money's worth in terms of cubic volume and sheer mass. The black upper-half creates a deception, and the amplifier doesn't look quite as big as it really is from the front; a three-quarter view reveals a unit measuring 416x117x334mm (whd). lt weights in at 9kg and the construction is nothing short of superb. I had a hard time not letting this luxurious presentation cloud my judgment, much in the way that I'm predisposed toward Beatles solo LPs.

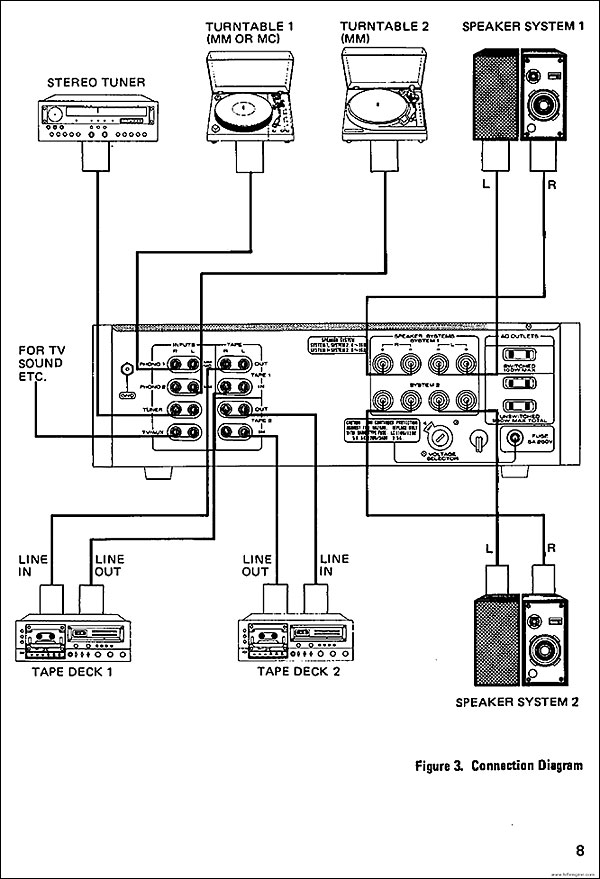

Ergonomically, the PM-4 was designed in such a way as to not give offense to minimalists, for the tone controls can be defeated. The fascia sports buttons for power and selection of up to two pairs of speakers, bass and treble controls, a group of toggles for tone defeat, tape dubbing (for two decks), and stereo/mono/reverse, two knobs for source selection and volume (with a balance control behind it), and three more buttons for Class A/AB selection, loudness (the one major lapse) and a subsonic filter. The front of the mesh cage houses a headphone socket.

Ripping Yarns

The back contains all of the necessary phono sockets, and the speaker terminals are stout binding posts that will only accept bare wire. Also of note are the two phono inputs, Phono 1 taking MM or MC cartridges and Phono 2 taking MM only. Overall, the design is a classic example of thoroughness, and I found no grounds for complaint other than that it's easy to tear one's flesh on the (necessary) massive heatsinks on the amp's sides.