Never too old

Conductors enjoy something of an advantage over their fellow musicians. Not just that they are better paid – to a degree that grinds the gears of their often more experienced orchestral colleagues the world over – but that the nature of their craft is relatively impervious to the ravages and indignities of age. Conductors can keep going until they drop. And quite often they do. Clarity of mind, force of will and the alchemy of charisma may elicit performances of remarkable insight from conductors who, in any other musical profession, would have bowed out gracefully decades earlier.

Fading fingers

The question of when to retire is understandably one that performing musicians can be reluctant to confront. For months I had keenly anticipated seeing Charles Rosen, one of my musical heroes, give a piano recital at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 2011. I walked out at the interval. The gap between what his mind still had to say about Chopin, and what his fingers could convey at the keyboard, was too great to endure. More recently, Maurizio Pollini’s final London recital descended into an embarrassing fiasco.

The process of embracing rather than postponing retirement can be an especially painful one in the case of singers, whose instrument is their own body, becoming (unlike a Strad or a Steinway) more unpredictable and unreliable with each passing year. Yet the relationship between a singer (especially a diva) and their audience can be so intimate that all rational considerations of graceful withdrawal can be swept aside in favour of one last farewell tour, or creaking appearance in a favourite role, and then another, all to frenzied ovations. We want our heroes to soldier on partly (at a subconscious level) because it proves to us that we, too, have life in us yet.

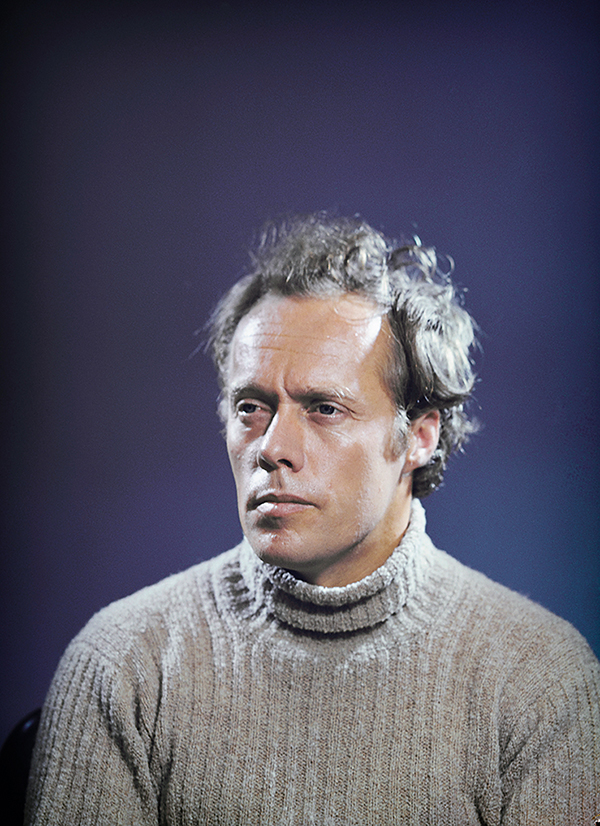

Finnish conductor Jorma Panula pictured in Helsinki in 1971 when aged 41 and [top] Swedish-born Herbert Blomstedt aged 97

There was certainly plenty of life left in both Jorma Panula (94) and Herbert Blomstedt (97) when I saw them conduct late last year. Both men walked to the podium unaided (in the case of Panula, climbing rather a steep set of steps up to the platform of Latvian Society House in Riga). There are some extenuating factors at work. Panula rarely subjects himself to the rigours of international travel, and instead specialises in the teaching of his craft, giving masterclasses in Helsinki and (now and again, such as in Riga) elsewhere in the region. Blomstedt’s staying power must be at least partly attributable to the rewards of clean living, following the precepts of a Seventh-Day Adventist, and a related principle of not rehearsing on a Sunday. Even so, their mastery over not only their own mind and body, but that of the score and the musicians in front of them, speaks for itself.

Leading with less

While their gestures are inevitably more minimal than those affected by their younger colleagues, there is no lack of energy in those gestures, which are directed always at the musicians, and never as a mirror to the musical gestures of the score. Panula and Blomstedt know, or at least convey the idea, that it is the musicians making the music, and not them. This communicates a humility and pragmatism that may also come with age.