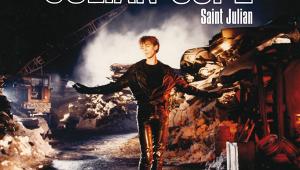

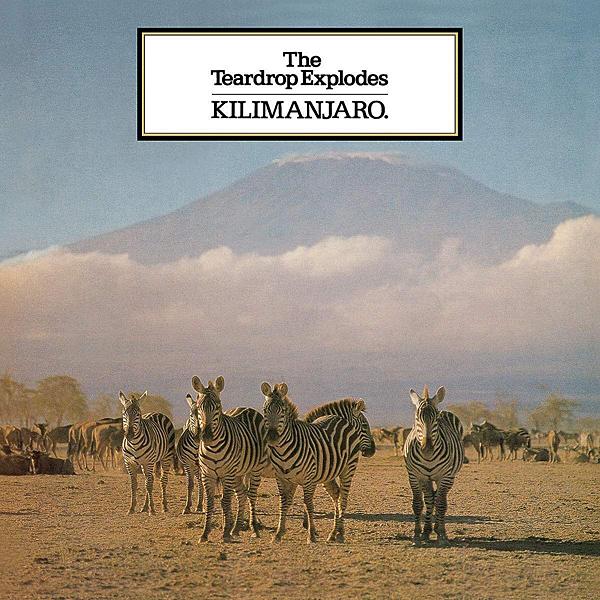

Teardrop Explodes: Kilimanjaro

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha…'

That's 26 'ha's and 31 'aha's. Go ahead, count 'em… 26 'ha's and 31 'aha's. That's precisely the number Julian Cope uses in his splendidly unsettling memoir Head-On to describe the making of Kilimanjaro, The Teardrop Explodes' debut LP.

Two paragraphs later, he writes: 'Aha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha aha.' That's 26 'ha's and just 18 'aha's. We'd let them all lie, but in the universe we're about to enter, this stuff is important. It might, in fact, have meaning (or, of course, it might not).

I know what you're thinking, but you'd be wrong. The good folks at Hi-Fi News don't pay me by the word. I'm listing all these 'ha's and 'aha's firstly in the pursuit of accuracy, and secondly to try to illustrate the utter, imbecilic, out of control mental state Cope and his band were in, when they attempted to put down on tape what was apparently a prolonged episode of what we might charitably call 'mind expansion'. Plus a rampant clash of personalities. Plus a festering bout of musical differences of epic, civil war proportions. And, thankfully, what also just happened to be a bloody fine record.

You see, Julian couldn't Cope. And that's the point of all this. I know from many years of writing that sex and drug tales aren't what you're after from this feature and – fair enough – we're here to do our duty to the record itself. But it's impossible, not to say criminal, not to acknowledge that Kilimanjaro is the consequence of what happened when Julian Cope – wet behind the ears and straight out of Liverpool Poly – was introduced to and really rather liked, first pot, then LSD. According to his book (now in paperback), the recording went a little like this: 'Every day we would wake up, take acid, then ride to the studio on our imaginary horses… "Hand me that spliff. I'm going to do all the singing dressed like Lawrence of Arabia".

'Actually I'd seen Sky Saxon, my hero from The Seeds, dressed like T E Lawrence in a picture. That inspired me. The vocals sounded ten times, no, 50 times better.'

The plan, according to co-managers and producers Bill Drummond (more escapades with the KLF down the road apace) and Dave Balfe (later Food Records supremo and Blur label boss), was to make an album, but once they all decamped to Rockfield Studios in the Welsh countryside, first came the unmaking of the band. Original keyboard player Paul Simpson had been chucked out and Balfe had usurped his part, and then guitarist Mick Finkler was replaced by Alan Gill from Liverpool legends-in-their-own-lunchtime Dalek I Love You.

Dark Secrets

The plan, according to Julian Cope at the time, was: 'The whole idea of The Teardrops to me is nice, nice melodies and lyrics that, while always sung hopefully, have dark secrets in them. I have this theory that we're the "lurking doubt" whispering in people's ears.'

And so to the great unravelling. These were the heady days of 1980, post-punk and anything goes and all that. The Teardrops had released two brilliantly tinny singles on Bill Drummond's scouse-centred Zoo label, then signed to Fontana where such great things were expected that the LP's working title was 'Everybody Wants To Shag The Teardrop Explodes'.

Off they went. Some of it was very nearly rubbish – 'Second Head' and 'Went Crazy' are acid babble and that's that. 'Sleeping Gas' and 'Bouncing Babies' are better, 'The Thief Of Baghdad' better still. 'Books' (Cope's version of 'Read It In Books', co-written with Ian McCulloch of pal/rivals Echo And The Bunnymen) is rampant. 'Treason' is the hit, fit to turn Top Of The Pops inside-out and upside-down. 'Brave Boys Keep Their Promises' is splendid, creepy and childish – and a throwback to, like, colonial times or something. Like the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band then, but cool instead of just plain daft.

The track 'Poppies In The Field' is outright awesome, crucified on a strident, repeating bass, blissed out on backwards guitar, locked into a flashback to the Second World War. It's a high that plants a flag on the summit of greatness.

Stoned Drivel

Strangely, all the worst things about Kilimanjaro are also the best things – the things that make it fab. The knobbly-kneed cod funk bass, the wurlitzer keyboards that invade every song in a bid to maintain their flagging momentum, the slash-flash guitar interruptions supposed to denote danger and chaos but far too predictable for that, and JC's plummy public school accent delivering stoned drivel as if it were cosmic profundity. Its goal is psychedelia, its achievement is unadulterated eccentricity, as English as Hornby train sets, Dan Dare and the Camberwick Green puppets.

Kilimanjaro is a group of adolescents role-playing at being unhinged rock stars and its hapless honesty shines through every awkward gesture. Julian Cope doesn't know who he is or what he wants, and he spends an awful lot of time on the album telling us so. It's tough when you fancy yourself as Jim Morrison but sound like Scott Walker's baby brother.

It's also frustrating when you aspire your band to be Arthur Lee's Love but you somehow hit the mark nearer The Hollies. As Donovan put it on 'Season Of The Witch': 'So many people to be'.

'I used to do outlandish, extreme things because that's what my heroes would have done,' Cope admitted later in a rare moment of clarity. 'The idea was that the accumulation of all my heroes would be one hell of a god to be!'

Don't get me wrong. This may sound like some damned failure but actually it's wonderful. I love Kilimanjaro the way I love Syd Barrett's stuff: because no matter how hopelessly wrong it is, it kind of can't help getting it right. The choruses are big and bright and unforgettable despite everything done to sabotage them. The vocals are so off they're on. They might have thought they were doing it for the 'ids' but it turned out they were doing it for the 'kids' despite themselves.

Another Universe

Look on the BBC website and they say this about Kilimanjaro: 'It inhabits a strange alternative universe that seems to have little relationship with contemporary sounds. For that reason alone it remains timeless'. Fair enough. And in one surprising recovery of something resembling good sense – or perhaps by pure accident – they saved the best for last.

'When I Dream' is glorious, not the least because, just like Gene Vincent's 'Be Bop A Lula' and Little Richard's 'A Wop Bop A Loo Bop A Wop Bam Boom', it proves that at its peak, pop ascends above and beyond language to an emotional telepathy all of its own. In case you haven't guessed, the chorus goes: 'Ba ba ba ba ba ba bada ba ba ba ba ba ba ba ba bada ba ba ba ba ba ba ba ba bada ba ba wow-o-oh!'.

Sheer Genius!

A little while after The Teardrops finished recording, Julian Cope suddenly realised he shared his initials with Jesus Christ. This was not entirely a good thing. The band did manage to make a second album in 1981 before it all went brains and belly up. Appropriately it was called Wilder and that one involved shotguns!

Re-Release Verdict

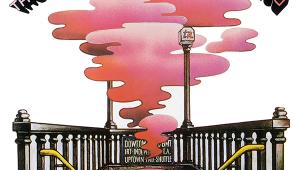

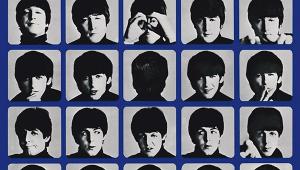

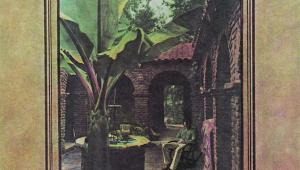

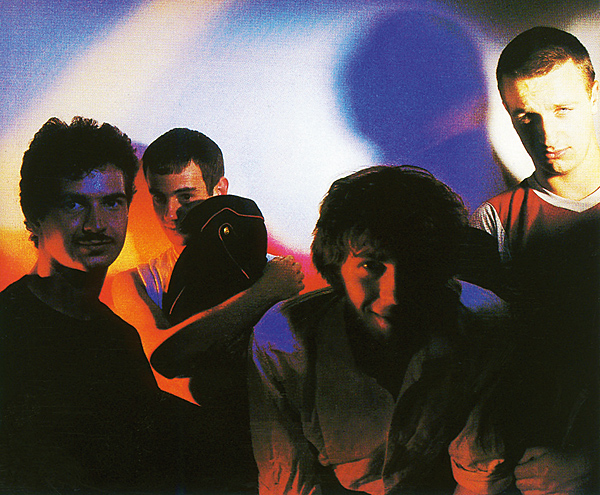

Kilimanjaro first came out in the UK in October 1980 on the Mercury label [6359 035]. It arrived in a mostly dark sleeve bearing a picture of the band's four members rather than the zebras of the alternative cover when 'Reward' was added to the album, which has been re-used for our UMC 180g vinyl reissue [776305 7] as seen here. Remastering was done at Abbey Road, and we enjoyed a flat, heavyweight pressing with no surface noise. HFN