The Great Replacement

It was the word homotonal that caught my eye. Surely no one writes like that in 2024, I wondered to myself. I read on. ‘Similar to Plato’s ideas of the imprint of moral virtues onto the human soul through music…’ – eh? Bear in mind I was reading a booklet note to accompany a new album of Mozart’s piano sonatas. I flipped the page to look for the author’s credit. No name given.

At the time of writing, my email to the record company to establish authorship has gone unanswered. So I will spare the blushes of the label (if they see any need to blush) and leave everyone concerned anonymous. I am, however, as certain as I can be that I had just read my first AI-generated booklet note.

Artificial Flavouring

The clues lay in the smoothly polished, impersonal tone; the assortment of pertinent but disconnected information; and the abrupt slips in that tone (‘After all, we don’t listen to good music just for fun; we tend to realise the importance of its message’) which give away the meaningless nature of that ‘we’.

You may read this as the futile protest of a grouchy hack, fretting over the source of his income. I had idly assumed that my chosen profession, of writing about music, was insulated from the march of AI. It takes human ears to listen to music made by humans, my reasoning went, and then to make sense of what they hear, using a human mind conditioned by personal but universal experience.

More fool me. After all, AI technology assists my work on a daily basis, as it does for almost everyone else. As it improves, transcription software is slowly easing the mind-numbing pain of typing out interviews with musicians. Translation software opens up instant access to previously inaccessible sources. An essay in a booklet about two long-dead Hungarian conductors? A little scouring of the ’net produced digital copies of their biographies, and – bingo.

Divine Intervention

Translators are among those at the sharp end of redundancy from artificial intelligence – which made it all the more curious that this anonymous booklet note on Mozart has been rendered into French and German by two indisputably human translators. Still, the record industry serves a market like any other, and consumers pay for what they want. If what you want is the music and the musician in up-to-date audio, then the packaging recedes into irrelevance.

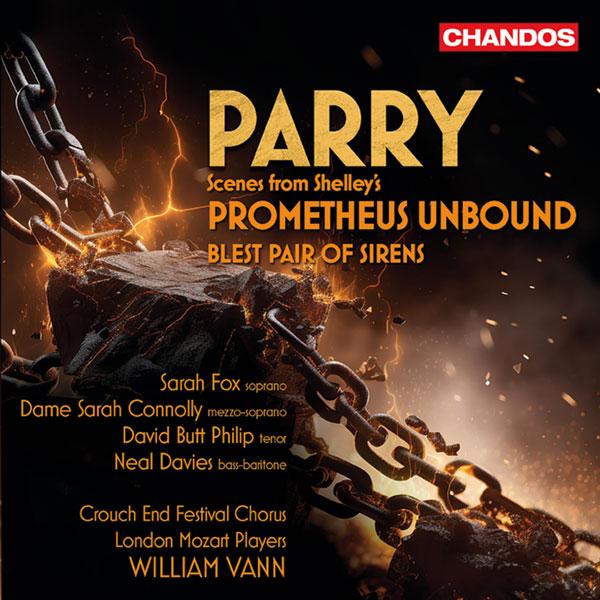

Chandos was upfront in crediting the cover image for its album of Parry’s Prometheus Unbound as ‘Original artwork created by the AI Midjourney with the assistance of Andy Brooks’. And why not? The cynic in me enjoys the irony of a collective e-brain used to illustrate the tragic myth of the man who sought to defy the gods by stealing divine fire in order to illuminate humanity with the gifts of creativity and technology.

The real-world portrait of Mozart, as painted by Joseph Lange (1783). The original hangs in the Mozarteum

If AI may be used to generate album covers, why not booklet notes? But then, why stop there? After all, recording engineers already use AI-adjacent technology in their work, to eliminate noises off, correct fluffs, smooth over the joins. Composers use software not just to write their music but to hear what it will sound like. I have encountered one dreadful example (now removed from the market) of a concerto album where the orchestral parts were MIDI-generated.

Can You See The Real We?

There is no reason why a record label shouldn’t release and sell Mozart sonatas played by an entirely virtual pianist, accompanied by entirely AI-generated packaging. Certainly no practical or commercial reason, at any rate. But as listeners, as record buyers, is that what we – a real ‘we’ this time – want?