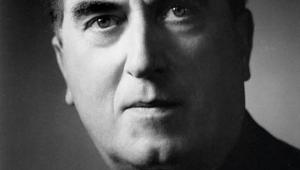

Ernest Ansermet Stereo Maestro

Ansermet made his first recordings in 1915, as a conductor of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes while on tour in New York, and always thereafter took a keen interest in the potential and the limits of recording technology. In September 1929 he became the first non-English conductor to make records for Decca, with a set of six Handel Concerti Grossi performed by a pick-up band at the Chenil Galleries studio in Chelsea.

Knockout Rimsky

In search of a glamorous roster of Continental maestros after the war, Decca lost no time in signing Ansermet back up. Early in 1946 he returned to London to record Stravinsky's Petrushka with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, produced by Victor Olof, who found him unlike any other conductor that he had come across. Compared to more hot-tempered colleagues, he remained entirely calm and unperturbed when a session was interrupted by a technical hitch.

'Ansermet had the art of perfectly balancing the various instruments of the orchestra and it was rarely necessary to make changes after a [microphone] test, thereby saving very valuable time', recalled Olof.

However, a conductor is nothing without an orchestra. Ansermet was 35 in 1918 when he founded the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande in Geneva. He rapidly coached it to an international standard, and over time into the instrument of his musical will. By 1954, the Ansermet/SRO combination had become the perfect vehicle for Decca to test a still-experimental recording technology. The resulting album of Rimsky-Korsakov's 'Antar' Symphony became the first of many early classics of the stereo catalogue. The depth of field and breadth of soundstage knocked listeners back in their seats at home.

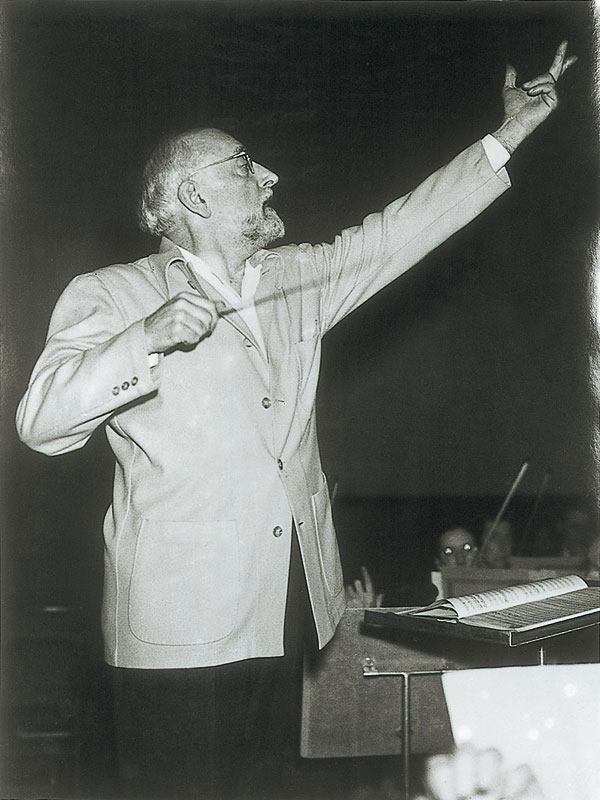

Ansermet was never knowingly wrong about anything – not unusual in itself, for a man of his time in his position. This, I think, made him less of a tyro to his players than an irritant to the composers of his acquaintance who had to endure niggly correspondence pointing out their 'mistakes' in this or that score. He had started out as a student and then an academic in the field of mathematics, in Lausanne. How could he have been anything else, with that high-domed forehead and neat professorial beard?

The combination of an analytical mind, calm temperament and sensitive ear made him the conductor he was. It also led him in later life to produce an attempted 'proof' that 12-tone modernism was 'not music' – a piece of pseudo-natural philosophy argued through maths and Husserl's method of phenomenology, further corrupted by anti-Semitic prejudice. Stravinsky broke off relations.

Sweep And Swing

Until his death in 1969, Ansermet continued writing, and poking around the hi-fi and LP stores of Geneva, in pursuit of new ideas and technologies. DSD and Spatial Audio would have found him in his element.

Pulse is an enduring virtue of Ansermet's conducting, as vital to the success of Haydn's 'Paris' symphonies (the first complete recording) as to Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty (Decca's ffrr sound at its sensational best) and to the music of the many composers he knew personally. There is always a sweep and a swing to his phrasing that draws you along.

He was a born ballet conductor even if he spent very little of his career in the theatre. In 1958 he remarked that the complete set of Delibes' Coppélia represented 'the happiest moments I have thus far spent in a recording studio'. To the symphonic ballets of Tchaikovsky he brought not only clarity and rhythmic impulse, but also those qualities which he was often thought to lack – tenderness and a sense of poetry, as if artistic sensitivity could not be reconciled with intellectual rigour.

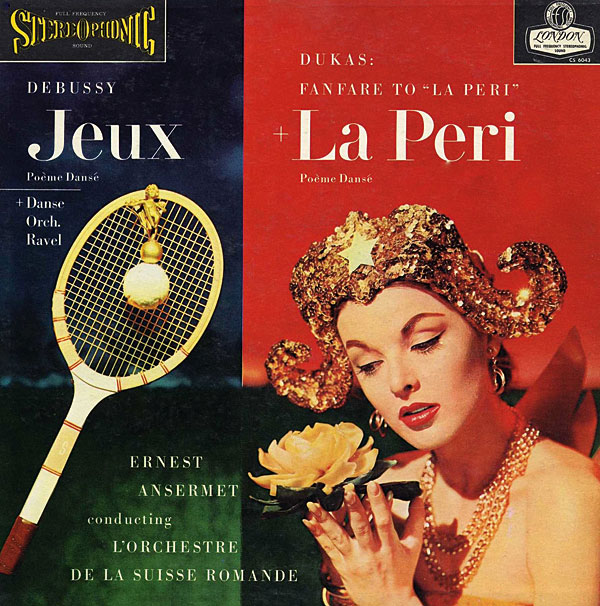

Ansermet had first met Debussy in 1910, and then they spent an afternoon looking over scores at the composer's house in 1917. Among postwar conductors, his interpretations (alongside those of Pierre Monteux) may lay claim to a special kind of authenticity. Against the grain of Debussy's reception, he underlined what he saw as the composer's debt to German composers – not only Wagner but 'the Bass-führung of Bach'.

Goal Directed

The new box that gathers up all of Ansermet's Decca stereo recordings throws light on his legacy from some unlikely angles. One of them is his interest in Bach – not just in thrusting accounts of the Orchestral Suites but in several under-rated cantatas whose performance values achieve a happy marriage between old-school grandeur and a dancing vivacity that belongs to this music in our own time.

This 'Bass-führung' – goal-directed voice-leading from the bottom up – is what distinguishes an astonishing Brahms First Piano Concerto captured live in Geneva (available here and there online) with Arthur Rubinstein. It is the pianist's most scintillating account of the solo part on record, and a vision of the piece as chamber music on an epic scale. It's also littered with errors arising from the heat of the moment, showing to posterity that Ansermet's studio perfectionism did not extend to control over the uncontrollable.

One postwar composer who was exempted from Ansermet's stringent criticism was Frank Martin – perhaps less for his shared Swiss heritage or his tonal method than the avowedly spiritual mission of oratorios such as Pilate and Le Mystère De La Nativité (coupled on a set from Cascavelle). Another was Benjamin Britten, whose War Requiem is perhaps the single most surprising entry in the conductor's discography but impressive for all that, shaped in smooth, rapid, chant-like arches.

Painfully Beautiful

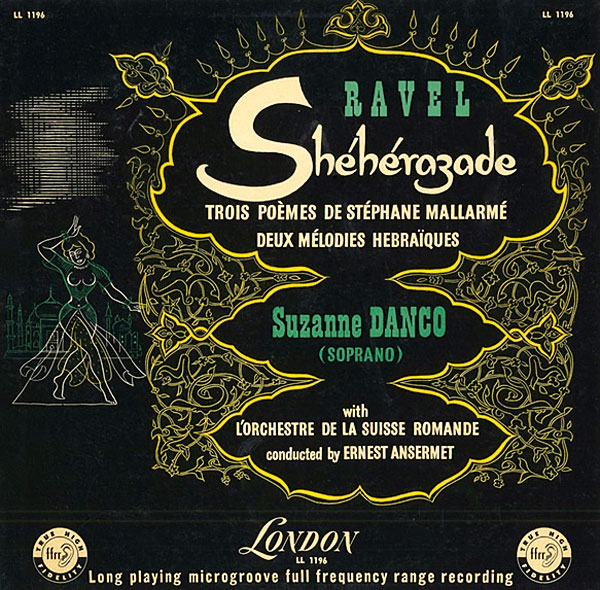

On the same Cascavelle set is Les Illuminations sung by Suzanne Danco, the soprano for a superlative Decca Shéhérezade and the Mélisande for Ansermet's recorded Pelléas. They shared a meticulous perfectionism, and she respected his demands for fastidiously clear diction. She is almost painfully beautiful as the Child for L'Enfant Et Les Sortilèges. The music of Ravel was a spirit animal for Ansermet. He understood its subtle craftsmanship, its clockwork mechanisms and its subterranean emotions perfectly.

By turn, some of Ansermet's last recordings reveal an unlikely affinity – a late-in-life coming to terms – with Brahms, who was no more interested than Ravel in wearing his heart on the sleeve of his music. Having now discovered it in this new set full of revelations, I would not be without the Decca German Requiem for its superbly sustained choral singing, the humility of Hermann Prey's solos and the spirit of humility which underpins the whole.

Essential Recordings

The Stereo Years

Decca 4851583 (88CD)

Gramophone classics from Haydn to Stravinsky meticulously documented and remastered, and in Decca's ffrr sound.

Ansermet Encores

Eloquence 4826158

Ansermet at his most genial in showpieces from Bach to Bartók – an exhibition of the composer's signature colouristic palette.

Debussy: Pelléas Et Mélisande

Eloquence 4800133 (2CD)

Suzanne Danco's unsurpassed Mélisande, and a timbral match for the conductor's strong lines and chiaroscuro in his first version.

Honegger, Brahms: Symphonies

Orfeo C202891

With the Bavarian Radio SO – a rare and instructive example on record of the conductor's work live and outside Geneva.

The Early Days

Cascavelle VEL3119 (8CD)

Rarities galore – and commensurately hard to find now – including the conductor's very first recordings from 1915.

Dutilleux, Martinù: Symphonies

Cascavelle VEL3127

His under-rated affinity for (particular) composers of his time, married to Ansermet's charismatic precision of gesture and timbre.