Bruckner Symphony No 7

Let's brush aside the old (but stubborn) complaint that Bruckner composed the same symphony nine times over. For one thing, he wrote 11 symphonies, only the first of which was intended purely as an exercise, and brought the last (numbered as the Ninth) tantalisingly close to completion. For another, each has its own personality, which is shaped by continual experimentation, his time of life, and the confidence and material accumulated by hard graft. Each successive symphony looks back on its predecessors and sets out on a different path.

All Of A Piece

Flow is the hallmark of the Seventh. With a very few momentous exceptions, the argument of the symphony unfolds in four closely inter-related spans, uninterrupted by the contrasts and juxtapositions which characterise the symphonies up to and including the Fifth. What 7 nonetheless shares with 5 is a sense of serenity in its progress. Even as the slow movement anticipates the soul-searching of the Adagios in 8 and 9, the eventual resolution of that pathos is never clouded by doubt or fear, as it is (or can be) in the later symphonies.

Bruckner achieves this wholeness through the familiar Romantic, cyclical tactic of thematic unity, the opening melody of the symphony bringing harmony and completeness to the coda of the finale. But he also does it by withholding radical modulations of harmony until late in the piece – just as Beethoven did in the 'Storm' of the Pastoral. The rhythms of the Seventh are also unusually regular for Bruckner, even in the skipping (or thundering) momentum of the Scherzo.

In the listening, it can easily be overlooked that the opening Allegro moderato sustains an unprecedented and audacious continuity of thought. There is no attack or pause for breath until well over halfway through the movement. The paragraphs unfurl like the pages of a Henry James novel. (James completed The Portrait Of A Lady in 1881, the year Bruckner began work on the Seventh).

Among renowned mono-era maestros, Furtwängler begins promisingly with a barely-there tremolo of expectation. The push-me pull-you tempo manipulation of first and second themes, however, shows him imposing a narrative that departs from the letter and (I think) the spirit of the score. He is doing too much, both with and to the symphony. By contrast, Günter Wand (RCA) adopts an attitude of scrupulous neutrality that he upholds through to a matter-of-fact conclusion. Both conductors were deep-thinking Brucknerians but neither was at home in the Seventh (indeed, Wand left it alone compared to the other mature symphonies, especially 5 and 9).

Happy Medium

The chosen basic tempo of that Allegro moderato has far-reaching implications for the whole symphony. At just over 15 minutes, Norrington (SWR-Music) produces a pliable, sweetly-toned, often plausible argument for the Seventh as a direct successor to the rustic Fourth, and something like Schubert's Fifteenth. At 21-22 minutes, Barenboim and Paavo Järvi persuasively draw parallels between the Seventh and Parsifal, premiered in 1882.

In between, around 18 minutes, Michael Gielen [see Essential Recordings, opposite] sets the Seventh in motion with an irresistible momentum that draws the ear smoothly through to the sudden crisis of C minor, 'like a great dam placed across a river' in Robert Simpson's phrase. This relatively swift basic tempo allows for episodes of relaxation and contemplation, then for a solemn but songful Adagio that never drags. This is followed by a finale of counterbalancing energy, where so often the movement feels either disproportionately protracted or too lightweight to bring full closure. Everything is connected.

Whether or not Bruckner heard Wagner's last opera before completing the Seventh, the symphony as a whole stands as a monument of gratitude and honour which became a tribute to Wagner's memory when he died in 1883, while Bruckner was still at work. Not only the use of Wagner tubas in the Adagio but also quotations in the finale make that relationship explicit. Karl Böhm was one of many interpreters to pull the symphony into a Wagnerian orbit – or Wagner as he was performed in the second half of the last century.

While the results are often grand and impressive, raised to a peak of sophistication in Thielemann's various Sevenths (three available on film alone), this approach misses the mark of the Seventh's distinctively gentle, burnished glow. Few pre-stereo recordings are worth investigating because most of them are either ill-played or undone by recorded sound which bleaches the copper and velvet from Bruckner's textures. Among them are two swift readings conducted by Paul Hindemith. These are fascinating documents all the same of a fellow composer getting inside Bruckner's head, and are representatives of an earlier Bruckner performing tradition relatively unburdened by angst.

Bernard Haitink conducted the Seventh throughout his career and I associate it with him more than any other piece. His many recorded versions each bear the stamp of their individual ensembles, varying considerably in details of tempo and articulation. But as with Gielen, all of them are animated by a strong and consistent pulse. His first version with the Concertgebouw retains a gripping, plain-spoken logic, but he reconsidered the Seventh one final time during the last year of his career, for performances with three different orchestras.

Peak Practice

These are happily preserved in different formats: the Netherlands Radio PO on CD, the Berlin PO on direct-to-disc LP (yours for around £500, if you can find it) and the Vienna PO on film. Haitink, at 90, brings an unmatched spring to the Scherzo, and builds the finale to a peak (before the coda) which makes new sense of the coda itself.

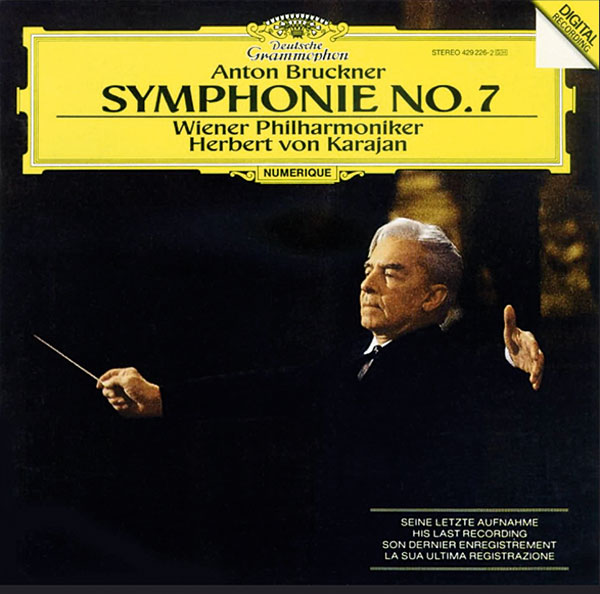

Bruckner conductors are made, not born. Herbert von Karajan's final recording was also with this piece, and with the Vienna Philharmonic, and is comparably illuminated by a lifetime's experience yielding fresh revelations with an orchestra who knew what he wanted almost before he did. By some alchemy of great age and intuition, Karajan keeps the fire burning under a very slow Adagio. Giulini, Skrowaczewski and Blomstedt all have their devotees when it comes to Bruckner, but here they stretch the music beyond the elastic of its natural syntax.

After 30 years of conducting the Seventh, Rattle has also tightened his tempi to positive effect. In this he was perhaps encouraged by the scholarship of the late Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, whose edition includes the cymbal crash and timpani rolls (at the climax of the Adagio) that acquire outsize significance for some listeners. More germane is the phrasing that never takes a 'Bruckner style' for granted, and the transparent engineering that reveals all parts of the LSO listening to each other.

Essential Recordings

Vienna Phil Orch/Herbert von Karajan

DG 4390372

Not as artificially spotlit as his BPO versions, more spontaneously played with a comparable fire to his late-stage Eighth.

Netherlands Radio Phil Orch/Haitink

Challenge Classics CC72895

Less orchestrally opulent than the late BPO and VPO versions, but still played with intense dedication and concentration.

SWRSO/Michael Gielen

SWR Music SWR19014CD (10CDs)

Solid German radio engineering and playing to support a shrewd vision of the Seventh without false trappings of grandeur.

London Symphony Orch/Sir Simon Rattle

LSO Live LSO0887

'Period' accounts by Herreweghe and Venzago notwithstanding, possibly the most transparent and rhythmically sprung Seventh.

Columbia Symphony Orch/Bruno Walter

Sony SMK64482

A pulse as natural as Haitink's, with a surprisingly flowing Adagio and trenchant finale. Close but not oppressive studio sound.

Pittsburgh Symp Orch/William Steinberg

DG 4864442 (19CDs)

In-depth, Command Classics sound from the '60s, newly remastered. 'American émigré' Bruckner, propulsive but never aggressive.